What makes Medieval and Early Modern Studies at Kent such a great place to study?

First and foremost, we make sure that we’re providing the best conditions for success and happiness for our students, whether they are undertaking a taught Master’s, a Master’s by research, or completing a PhD.

Because the Centre for Medieval and Early Modern Studies (MEMS) is an interdisciplinary centre that means making sure everyone in our broad church feels included and supported. It also means communicating closely with the staff who make MEMS tick – the professional services team who take such good care of students and academics alike – and the teaching staff who contribute so much to upholding the excellent reputation of our Centre through their teaching and research.

What do you enjoy about teaching on the MA Medieval and Early Modern Studies and teaching in Paris?

Teaching on the MA is the kind of teaching we love to do. We look at materials that we actively research, and get to share our own interests and (hopefully!) expertise with the students. We also get to see students gain confidence as they approach materials using methods that they will not have experienced as undergraduates. We see them learn new skills and transition into proper researchers in their own right.

As for teaching in Paris, what can one say? You’re teaching in a wonderful setting, a campus in the heart of a beautiful, vibrant and historic city, surrounded by incredible resources for teaching pre-modern studies – manuscripts, art, architecture. And the food isn’t bad either. C’est magnifique!

What do students say about studying Medieval and Early Modern Studies?

I think the main benefit has to be our sense of community. Our Centre comes together each Thursday afternoon/evening for our very popular seminar giving an opportunity for staff, MA and PhD students to mix. There is almost always some sort of event being run in the Centre, which multiplies these opportunities for conversation and for intellectual exchange. The highlight of the academic year is the MEMS Summer Festival, a two-day conference completely organised by PhD and MA students (and which was the brainchild of a former student).

At MA level, students benefit from being part of a relatively large cohort – our programme attracts a large and diverse body of students every year. These numbers mean we can run a variety of option modules as well as having a full-time permanent member of staff providing all the core teaching. Students quickly form strong bonds and cluster together outside of contact hours both to study and to have downtime together.

In some respects, the benefits are similar at PhD level. We have an excellent track record in getting students funded to PhD scholarships, meaning there is a populous and strong PhD community, who are very proactive in devising, organising and supporting events (and who attend international conferences en masse!) Most importantly, they are most proactive in supporting each other through the journey of doctoral study.

What are your main research interests?

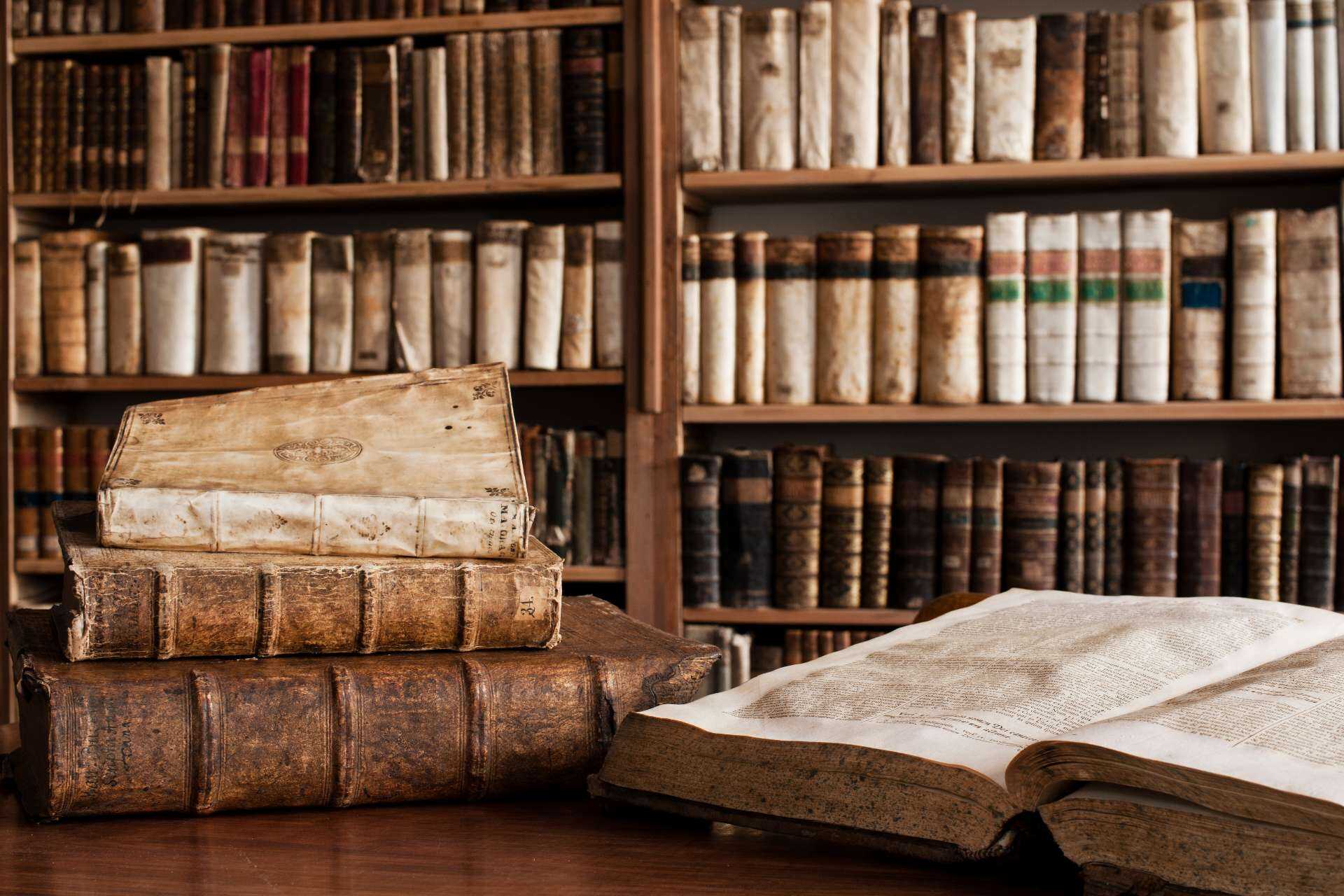

Primarily I am interested in what I would call Middle English manuscript cultures – that is, looking at the varied production, dissemination and reading circumstances of texts penned in the English vernacular between the 14th and 15th centuries. This has allowed me to look at diverse genres of manuscript books – chronicles like the popular British History, the prose Brut, and devotional religious texts such as Nicholas Love’s Mirror of the Blessed Life of Jesus Christ. Most recently I have become fascinated by the explosion in production of vernacular religious anthologies in 15th-century London. These books were made for the benefit of the City’s mercantile and artisanal classes. They tend to be plain and work-a-day, covered with the stains of everyday life – wax, egg and even gravy can sometimes be distinguished on their leaves, and they often have scribbled calculations and other pen trials in the margins and outer leaves. They’re not the sumptuous art objects like illuminated Books of Hours that one sometimes associates with the Middle Ages, but I identify more closely with their lived-in and utilitarian qualities.