Up and Atom: Las Vegas and the Bomb

Up and Atom: Las Vegas and the Bomb

by Dr John Wills

Illustration by Go Vicinity Creative

Images courtesy of Las Vegas News Bureau

Throughout the 1950s, the US military conducted over one hundred atmospheric nuclear tests on continental soil. At Nevada Test Site (NTS), radioactive mushroom clouds loomed high above the scorched desert. In retrospect, it is easy to dismiss America’s atmospheric testing in the fifties as a woeful instance of Cold War sabre rattling, designed to intimidate the Soviet Union but with little scientific or military justification.

Atomic Experimentalism

However, each test entailed a wide range of civilian, scientific and military experiments designed to further understanding of radiation, as well as prepare the nation for the grim eventuality of nuclear war. The format of the experiments varied greatly and included placing automobiles at a range of distances from ground zero to judge their survivability (leading to the civil defense pamphlet ‘4 Wheels to Survival’), exposing tinned food to high levels of radiation (with post-explosion taste testing!), and caged pigs being immolated to predict human skin damage.

Troops themselves fell prey to a marked fascination with atomic experimentalism, becoming ad-hoc guinea pigs on the atomic battlefield.

The US Federal Civil Defense Administration (FCDA), tasked to ensure the nation survived atomic attack, even constructed fake townscapes at NTS in 1953 and 1955. Its ‘survival towns’ (dubbed Doom Towns by the press) were only made possible by corporate donation, with the department store JC Penney proudly dressing mannequin denizens in the latest fashions, with the proviso that future clothing styles might be shaped by their ability to afford some protection from radiation.

Living close to such experimentalism in the 1950s carried significant risk. At settlements such as Saint George, Utah, 135 miles east of ground zero, ‘downwinders’ suffered a range of health maladies due to westerly winds carrying radiation toward them.

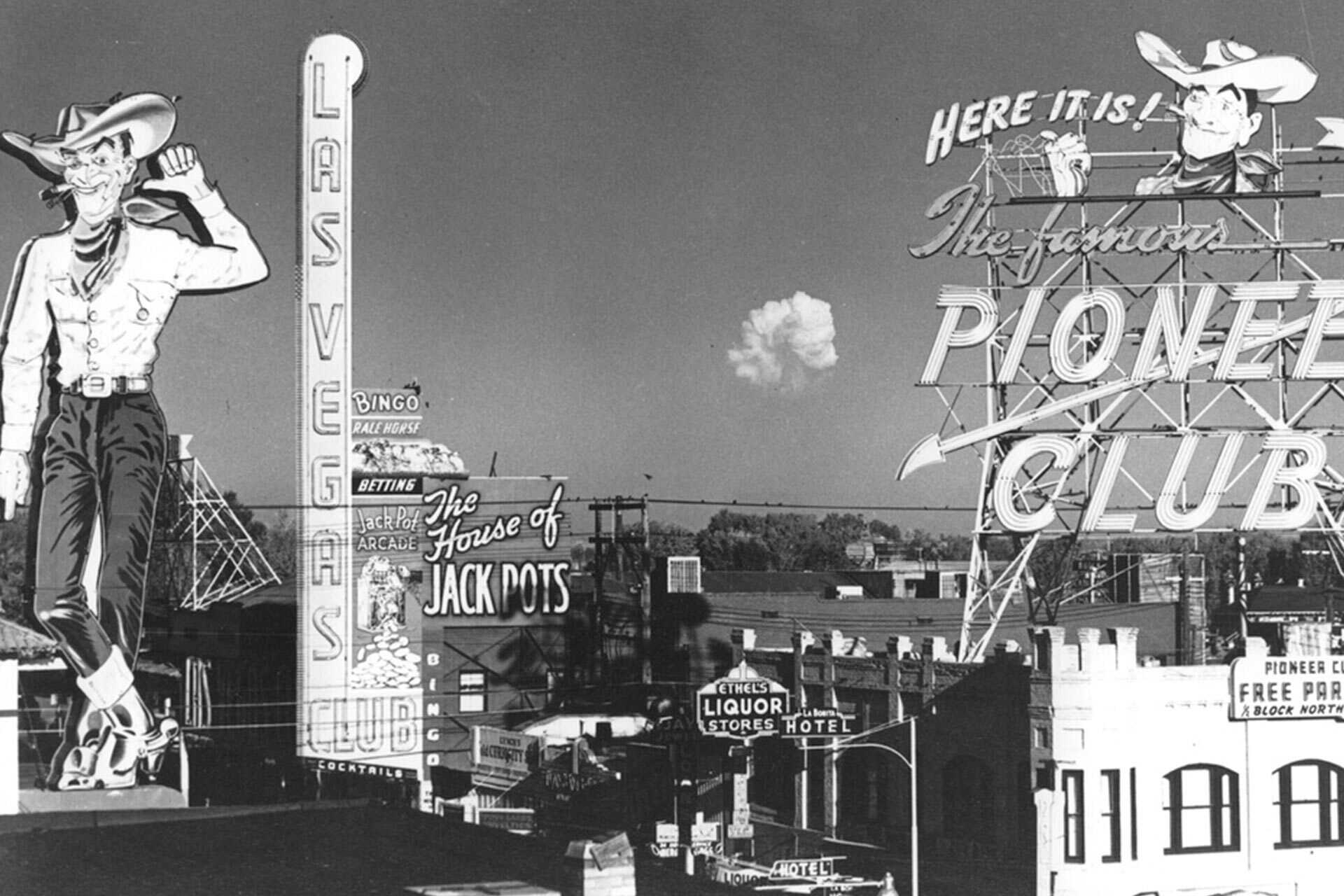

However, at Las Vegas, just 65 miles south of the test site, the story proves quite different. Most atomic blasts could be seen from Sin City, but the radioactive clouds stayed at a safe distance. Meanwhile, Las Vegas entrepreneurs annexed the nuclear age for their own commercial agenda.

Thanks largely to mob money, big name shows, and new ‘themed’ casinos, Las Vegas in the 1950s was a booming city.

Atomic city

Initial wariness over military activities at Nevada Test Site dissipated thanks to a combination of official reassurance, employment prospects, and business opportunities. Locals quickly adjusted to living in a new ‘Atomic City.’

At the Flamingo casino hotel, journalists formed the Ancient and Honorable Society of Atom Bomb Watchers in April 1952, pledging to “keep forever the secrets” of the A-Bomb, as well as their own evening activities in Sin City, with a group password of ‘cimota’ (or ‘atomic’ backwards).

Meanwhile, tourists flocked to Vegas not just for the prize fights and gambling opportunities, but to watch the “atomic firework display” go off at sunset from the relative safety of the hotel poolside. Casinos such as Binion’s Horseshoe held ‘atomic pool parties’ whereby guests partied into the night, then raised their glasses as a mushroom cloud ascended in the distance.

Sin City appropriated the bomb for its own thriving entertainment culture, transforming the test series into an unlikely vehicle for profit and popular amusement.

Although the exact origin is unknown, Atomic Liquors on Fremont Street was certainly one of the first places to sell the atomic cocktail, a mix of vodka, brandy, sherry, champagne and dry ice, while the Flamingo Casino’s beauty parlor provided mushroom-type hairstyles.

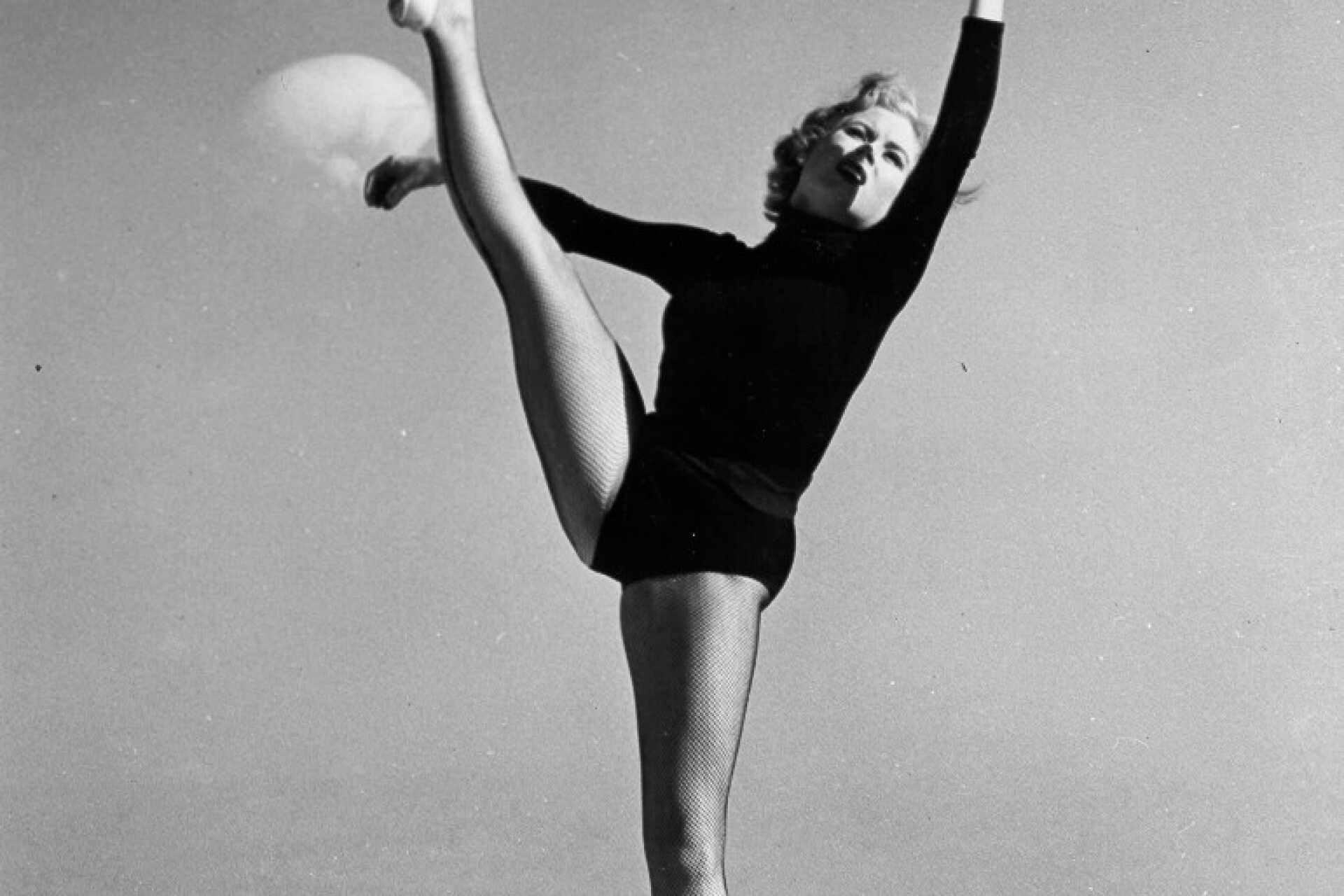

In May 1952, Las Vegas dancer Candyce King became the first in a series of ‘atomic pin-ups’ when she entertained troops at the Last Frontier and gained the epithet ‘Miss Atomic Blast.’

Operation Plumbbob

Photographed at the Sands Hotel in May 1957, Lee Merlin celebrated the 1957 Plumbbob series, the peak of atmospheric testing, by sporting a swimsuit with a giant fluffy cotton mushroom cloud (the design of the modern bikini owes its inspiration to the atomic bomb). Such sexualization of the bomb suited masculinized military culture of the day; it also downplayed the significant dangers.

However, by the time of the 1957 test series, nuclear tourism in Vegas had already begun to wane. Reading local newspapers from the time reveals a marked rise in skepticism over assurances of public safety by the US military. Las Vegans were fast falling out of love with all things atomic. Their rejection of the bomb was part of a broader shift in attitude toward nuclear testing.

Within a few years, the United States and Soviet Union had signed a treaty banning all above-ground atomic explosions. The radiation and the cocktails nonetheless lingered.

About the author

Dr John Wills is a scholar in US cultural and environmental history and the author of six books. He is currently writing a monograph on nuclear testing for University of Kansas Press. His research and teaching interests bridge several disciplines, most notably history, sociology, cultural studies and game studies.