Exhibition - Victorian and Edwardian Pantomime

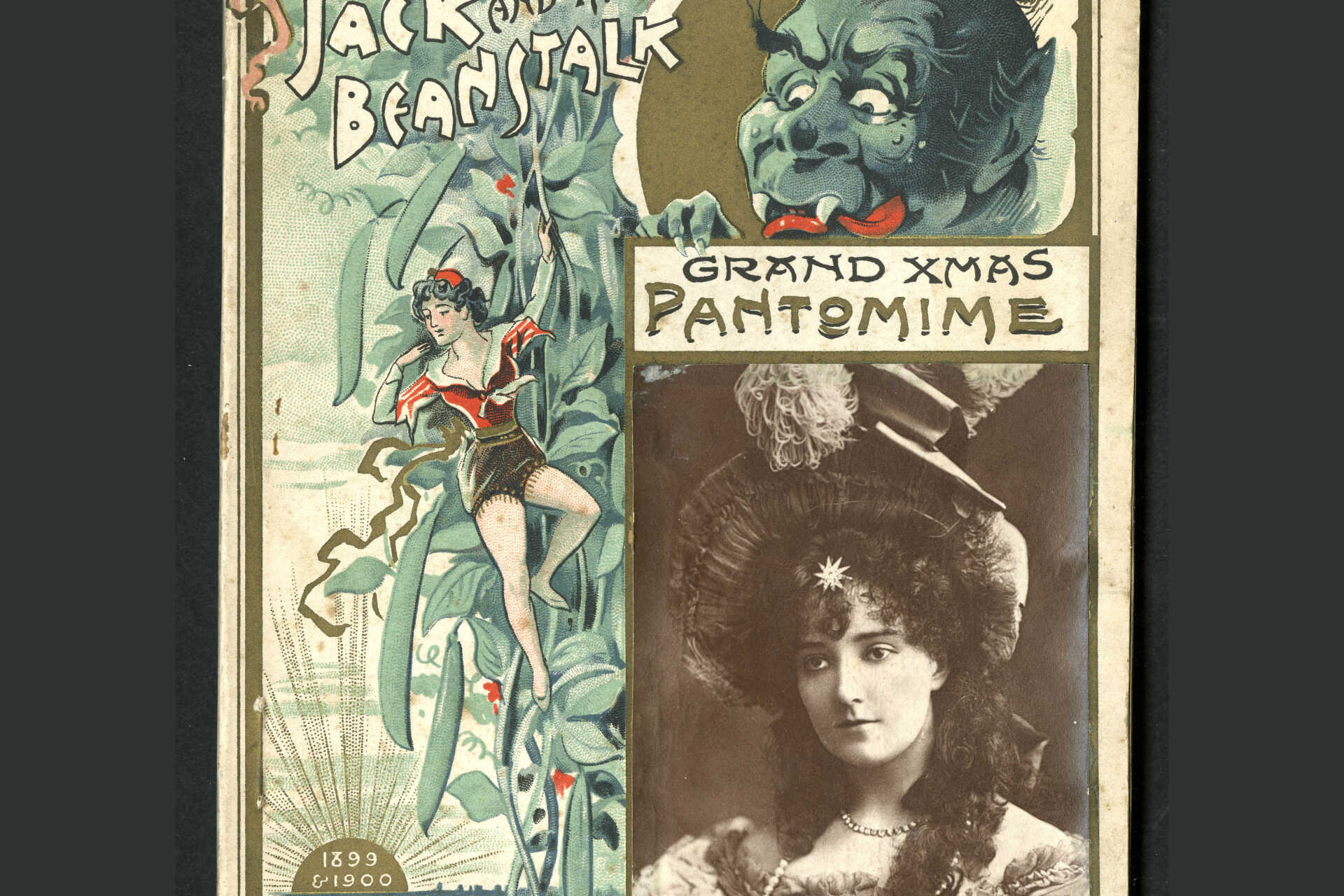

In this section we'll be exploring Victorian and Edwardian pantomime, with a focus on those that were instrumental on making it such a popular form of entertainment during the period.

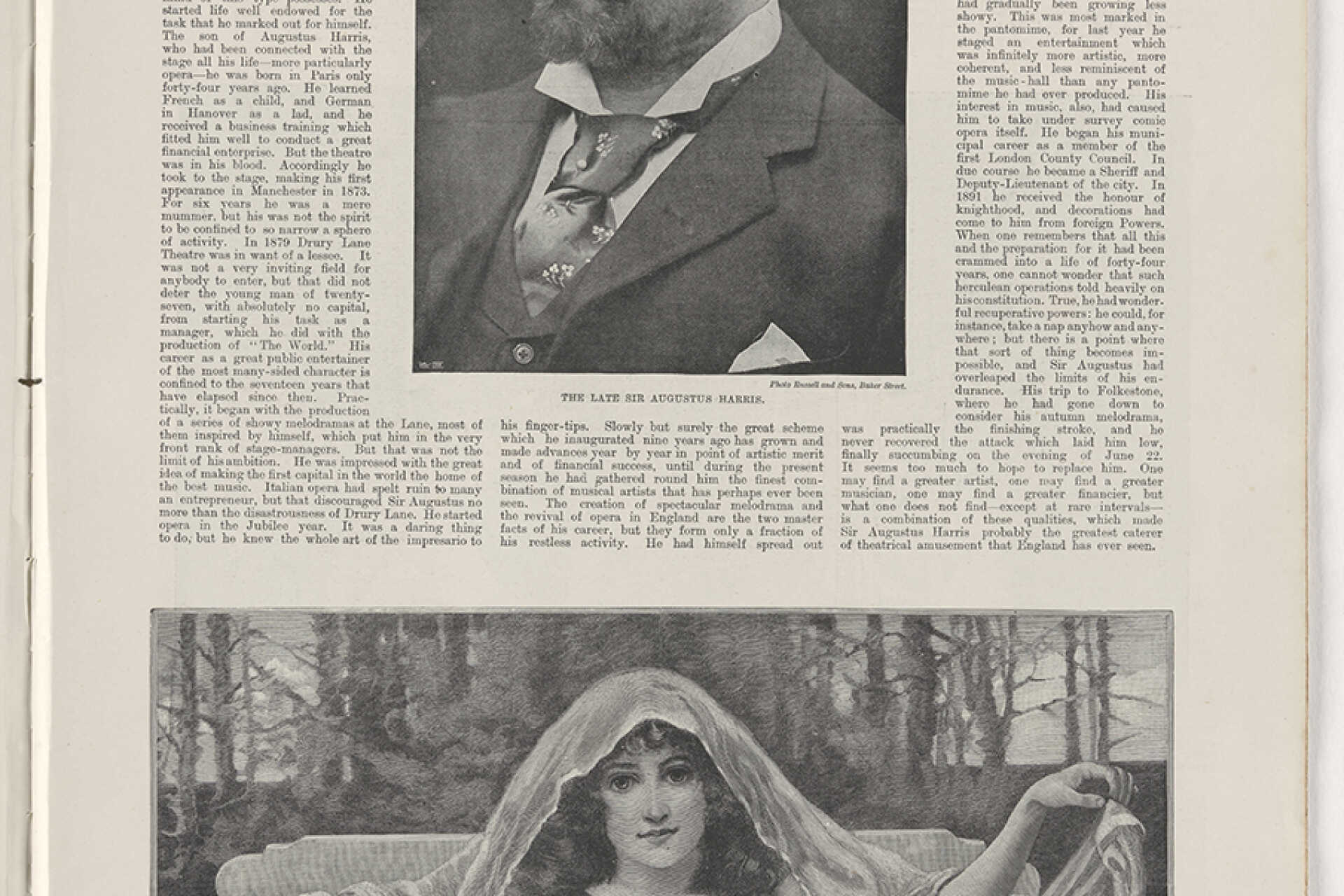

Sir Augustus Harris and the Drury Lane Pantomime

Sir Augustus Harris (1852-1896) was a British actor and dramatist. Born into a theatrical family - his father, Augustus Harris Snr, was a comedian and stage-manager and his mother, Marie Ann Bone (aka Madame Auguste) was a dancer and costumier, Harris began his theatre career in 1873 when he debuted as an actor in the Manchester Theatre Royal’s September production of Macbeth, playing the role of Malcolm.

After working as an actor and stage-manager, Harris moved into theatre management 1879, when he became licensee of the then empty Theatre Royal Drury Lane at just 27 years old. Harris’ first show at Drury Lane was to be the Christmas pantomime – by then a Drury Lane Christmas institution – and he pulled all of his resources together to put on an extravaganza! The story he settled on was ‘Bluebeard’, which was received with praise…

“Blue

Beard has come, has been seen, and has conquered; the laughter and applause

that greet the efforts of the actors and actresses, the shouts of delight as

each spectacular feature of the Pantomime comes under the notice of the

audience… all contribute to prove the fact that author and actor, Manager and

scenic artist, indeed all concerned, have in their several vocations done their

best, and, for a reward, have the satisfaction of knowing that their patrons,

unlimited in number, are delighted with their work.”

The

Era, 1st February 1880, Issue 2158

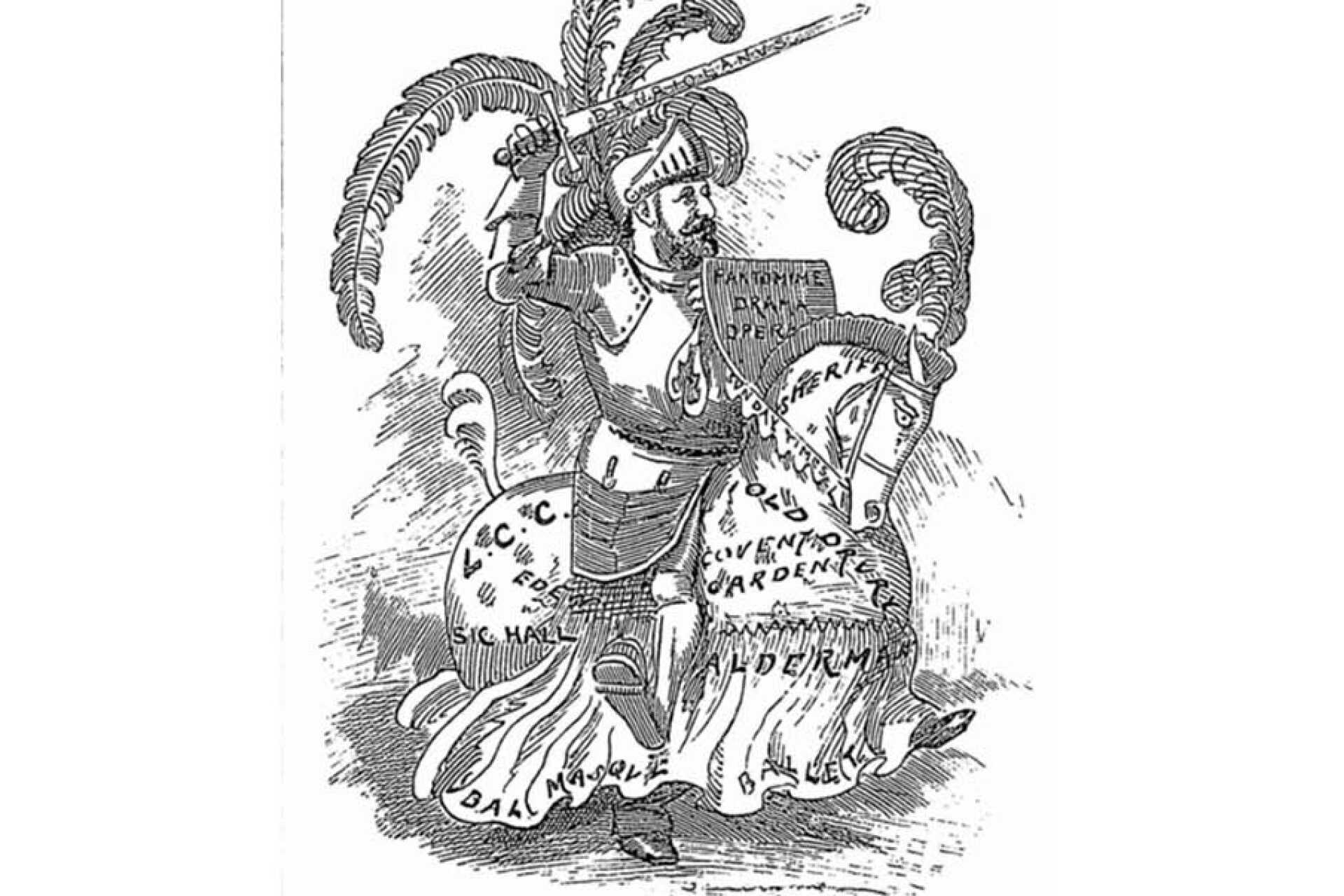

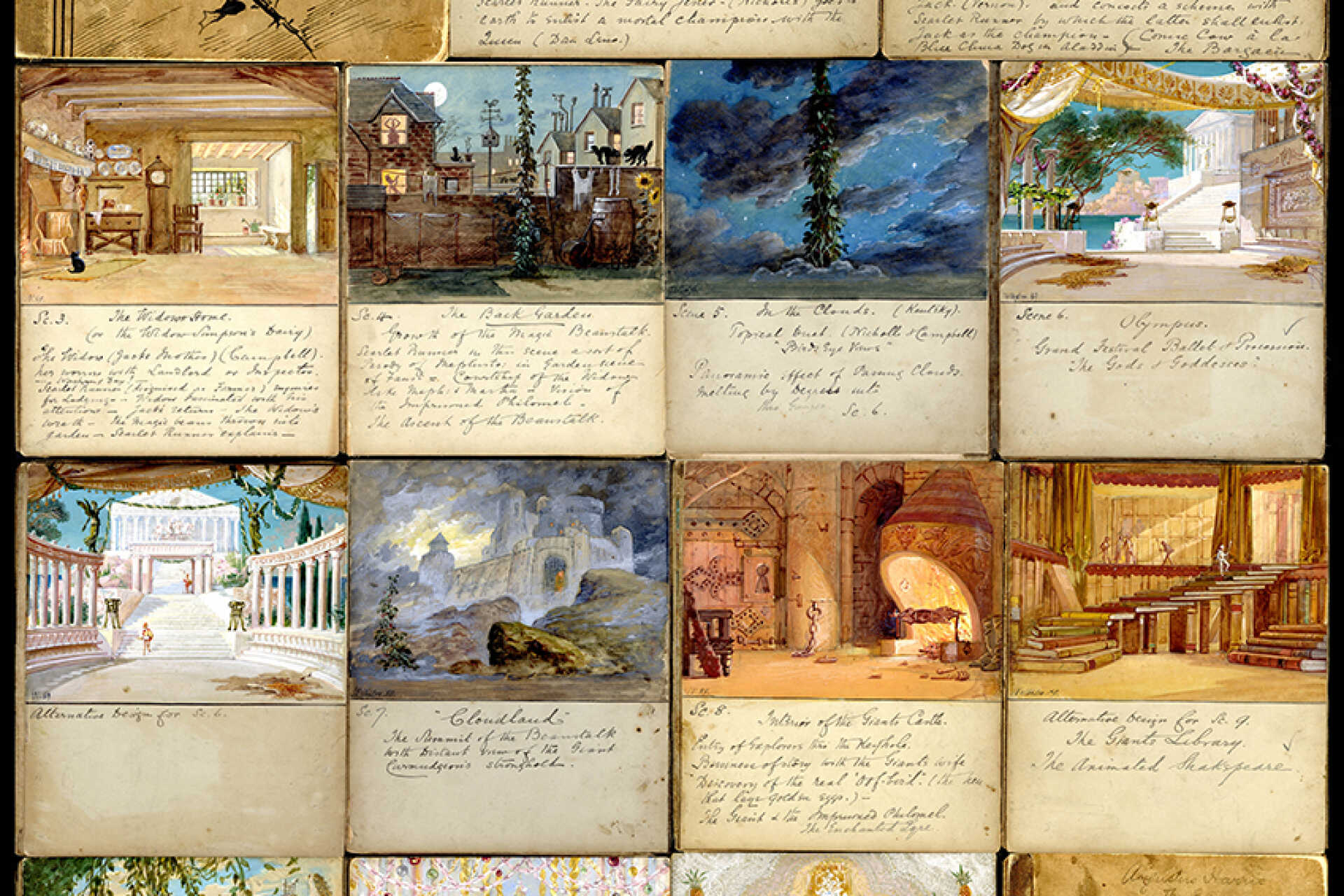

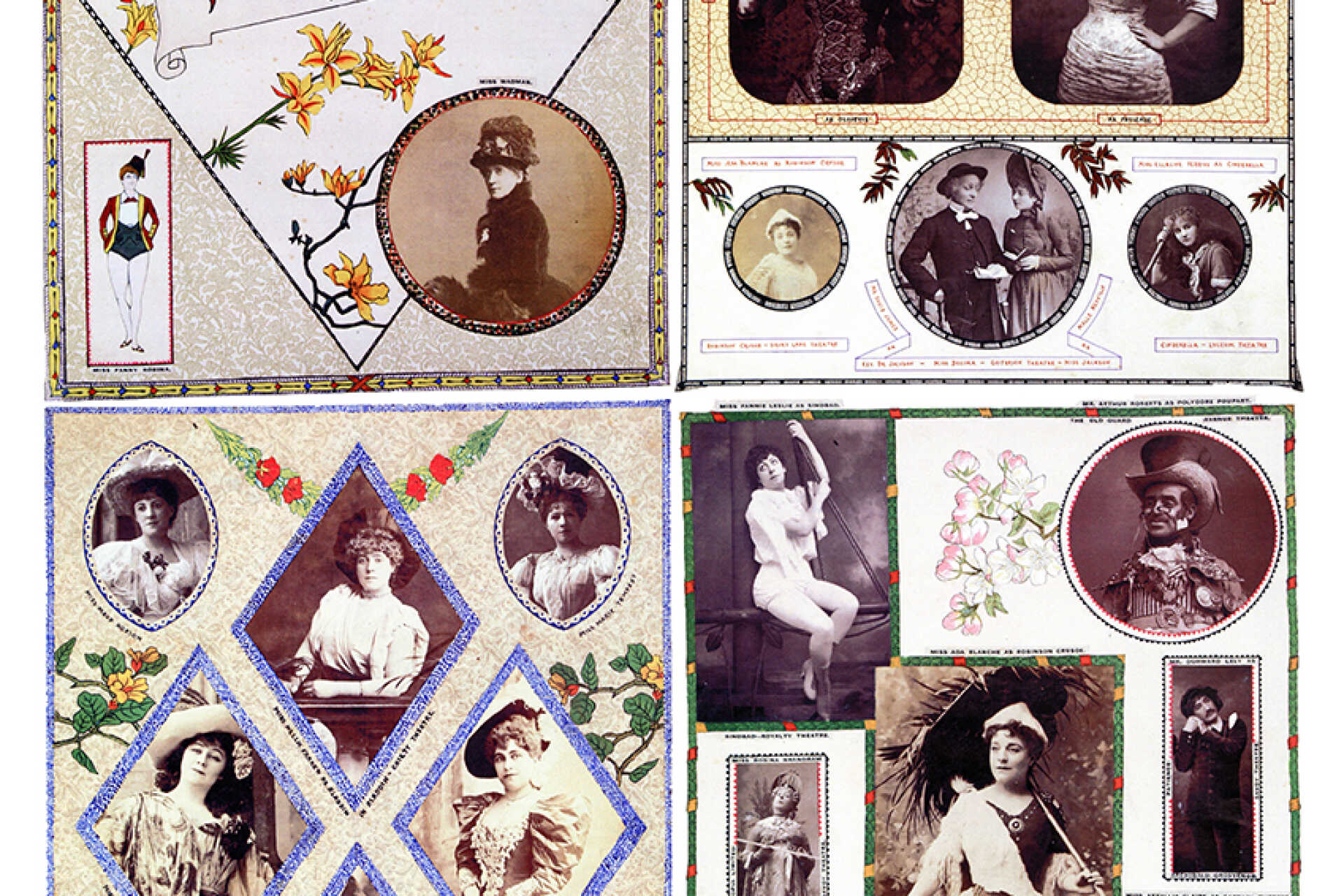

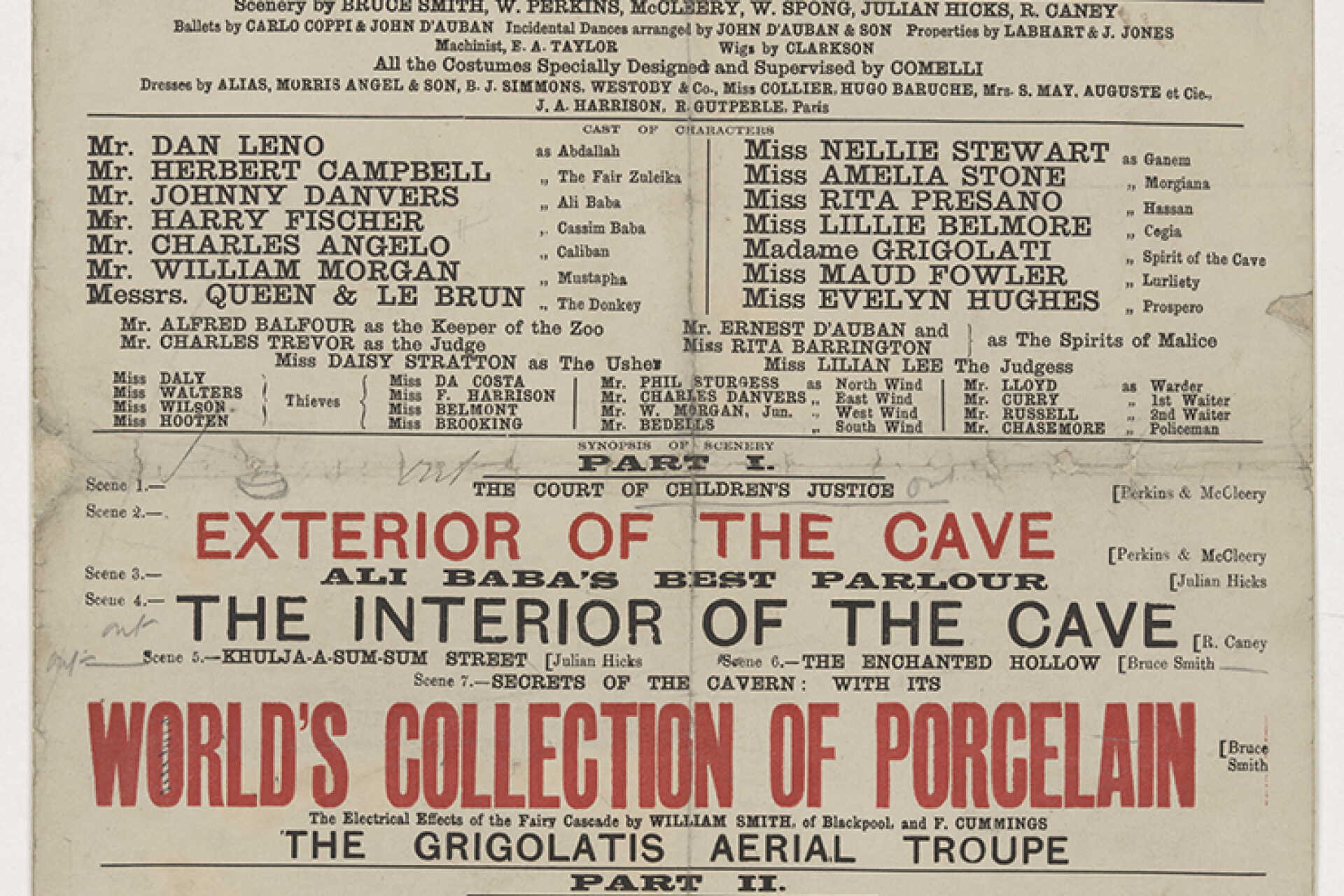

Harris continued to put on Pantomimes each subsequent year on a continually impressive and spectacular scale. They took months of planning, featuring expensive and elaborate set designs, and impressive processions that often-involved hundreds of people being on stage. They would typically cost between £6000-£8000, which can be estimated as around £1million in today’s money. In the 1890 production of ‘Beauty and the Beast’ an enormous ship was even brought onto stage! These fantastic productions earned him the nickname the “Father of Modern Pantomime”, alongside his usual moniker of “Druriolanus”.

In addition to his magnificent pantomimes, Harris produced a dramatic production at Drury Lane each Autumn, which proved lucrative and successful, and produced many operas. His dramas went on to be staged in provincial theatres across England, toured America, and three were made into films well after Harris’ death. He also managed other theatres, sometimes simultaneously, including Her Majesty’s Theatre, Covent Garden, and the Olympic.

Alongside his theatrical achievements, Harris became a member of the London City Council and was appointed sheriff of the City of London in 1890. He was knighted by Queen Victoria in 1891 and was a prominent freemason.

Harris died in Folkestone in June of 1896 at the Royal Pavilion Hotel at the age of 44. His funeral featured a grand procession, starting from his home in Primrose Hill to his burial place at Brompton Cemetery, along which several thousand people from all walks of life lined the pathways.

“It seems too much to hope to replace him.

One may find a greater artist, one may find a greater musician, one may find a

greater financier, but what one daoes not find – except at rare intervals – is a

combination of these qualities, which made Sir Augustus Harris probably the

greatest caterer of theatrical amusement that England has ever seen.”

Illustrated London News, 27 June 1896, p. 805