Exhibition - The Rise of Facism

Dr. Amy Matthewson explores the rise of fascism through the lens of cartoons, highlighting how humour acted both as a powerful tool of social control but also of resistance and defiance in the face of oppression and uncertainty.

The Power of Cartoons: Introducing Sir David Low

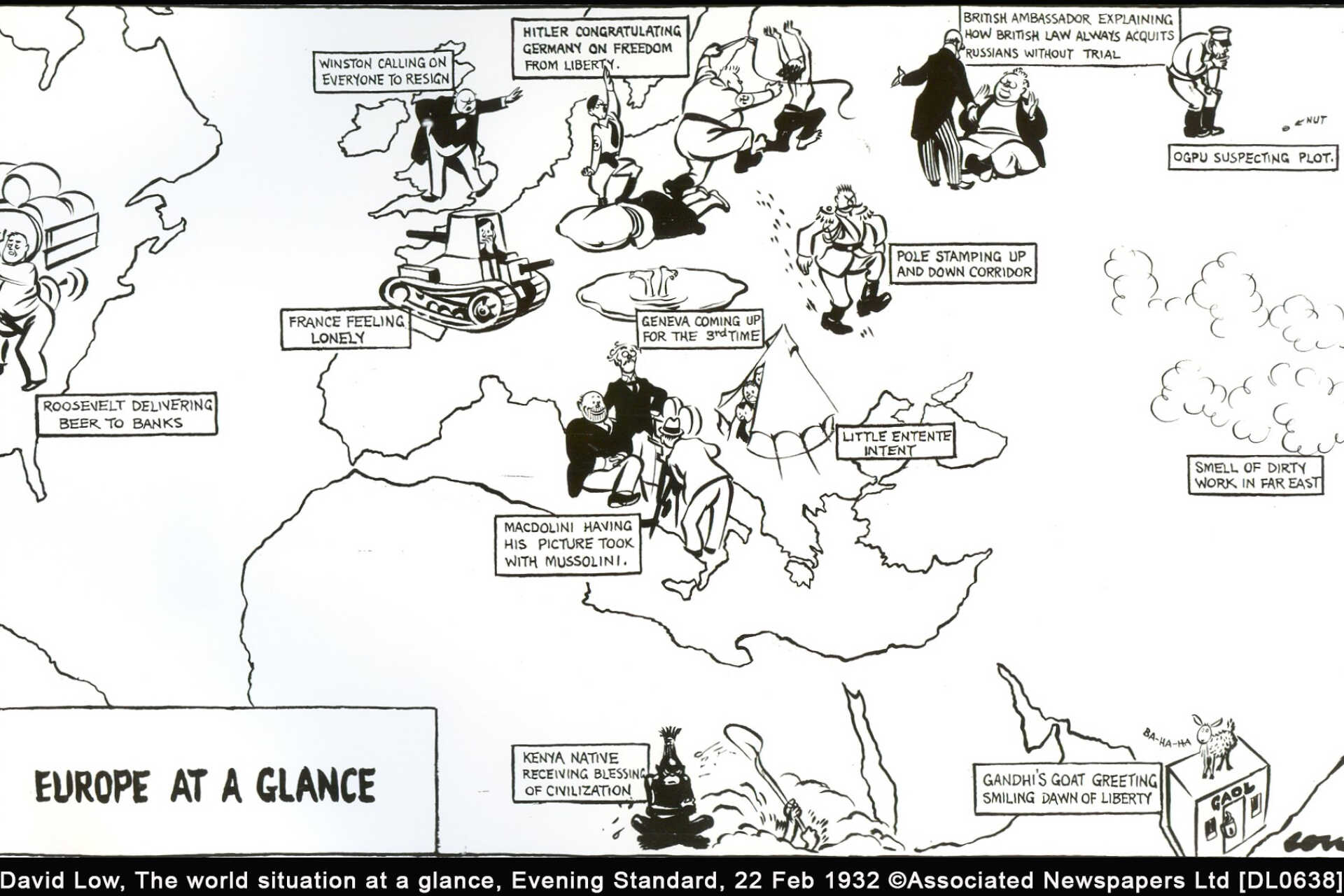

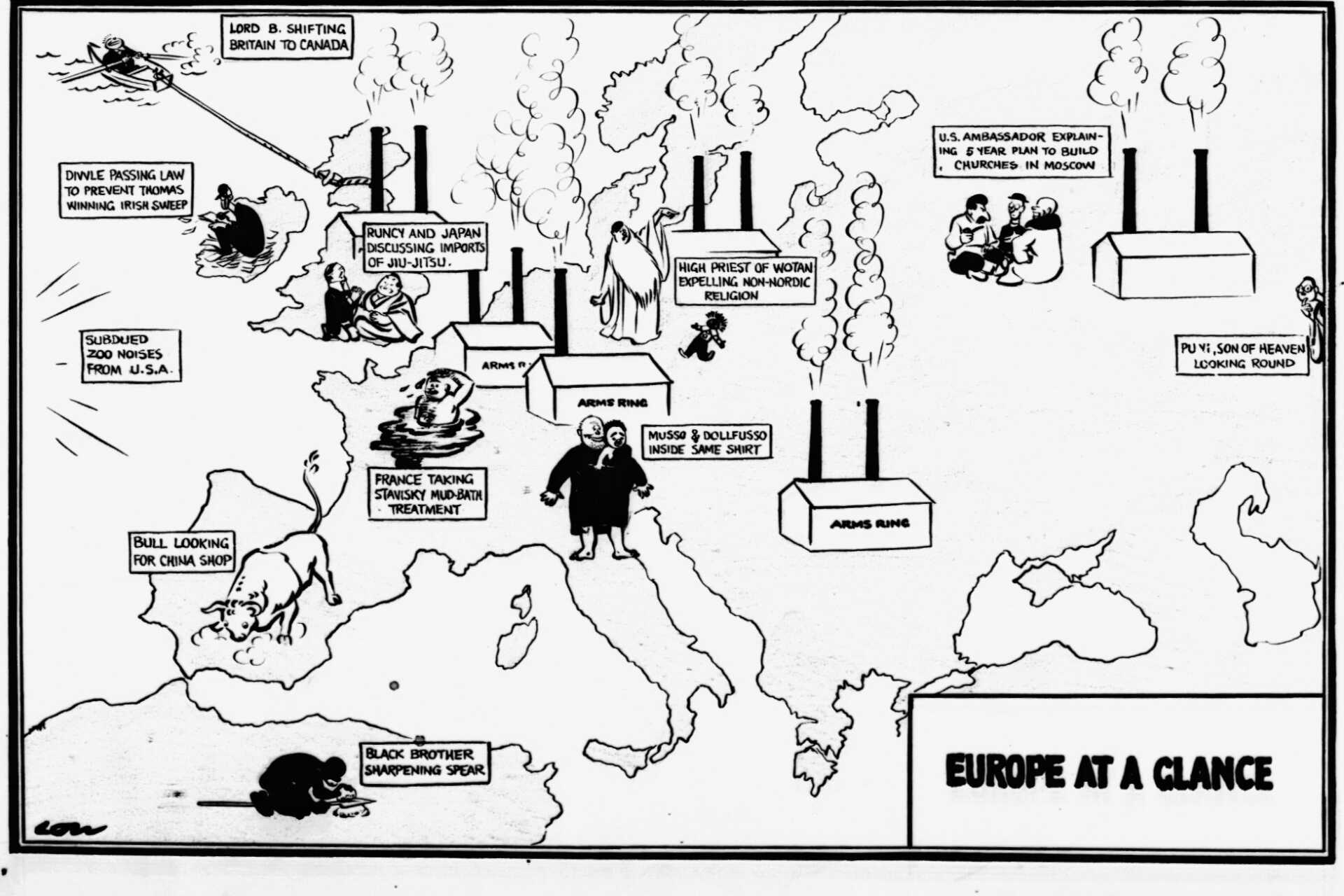

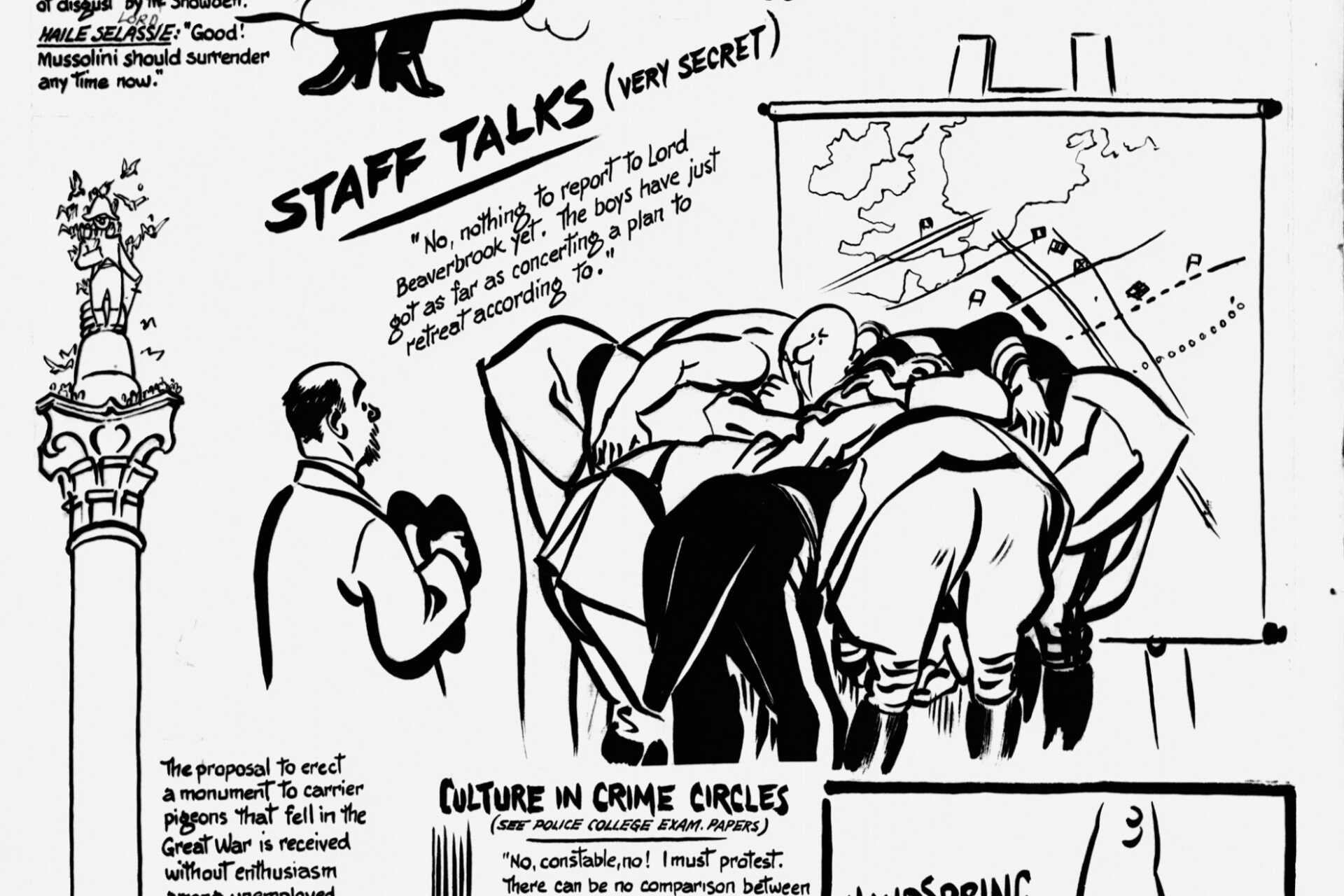

Cartoons have long served as powerful tools of resistance. Napoleon reportedly said that the English caricaturist James Gillray “did more than all the armies of Europe to bring me down.” The cutting witticism and accessibility of cartoons present a unique power to challenge governments, critique ideologies, and galvanize the public towards or against a person, policy, or event.

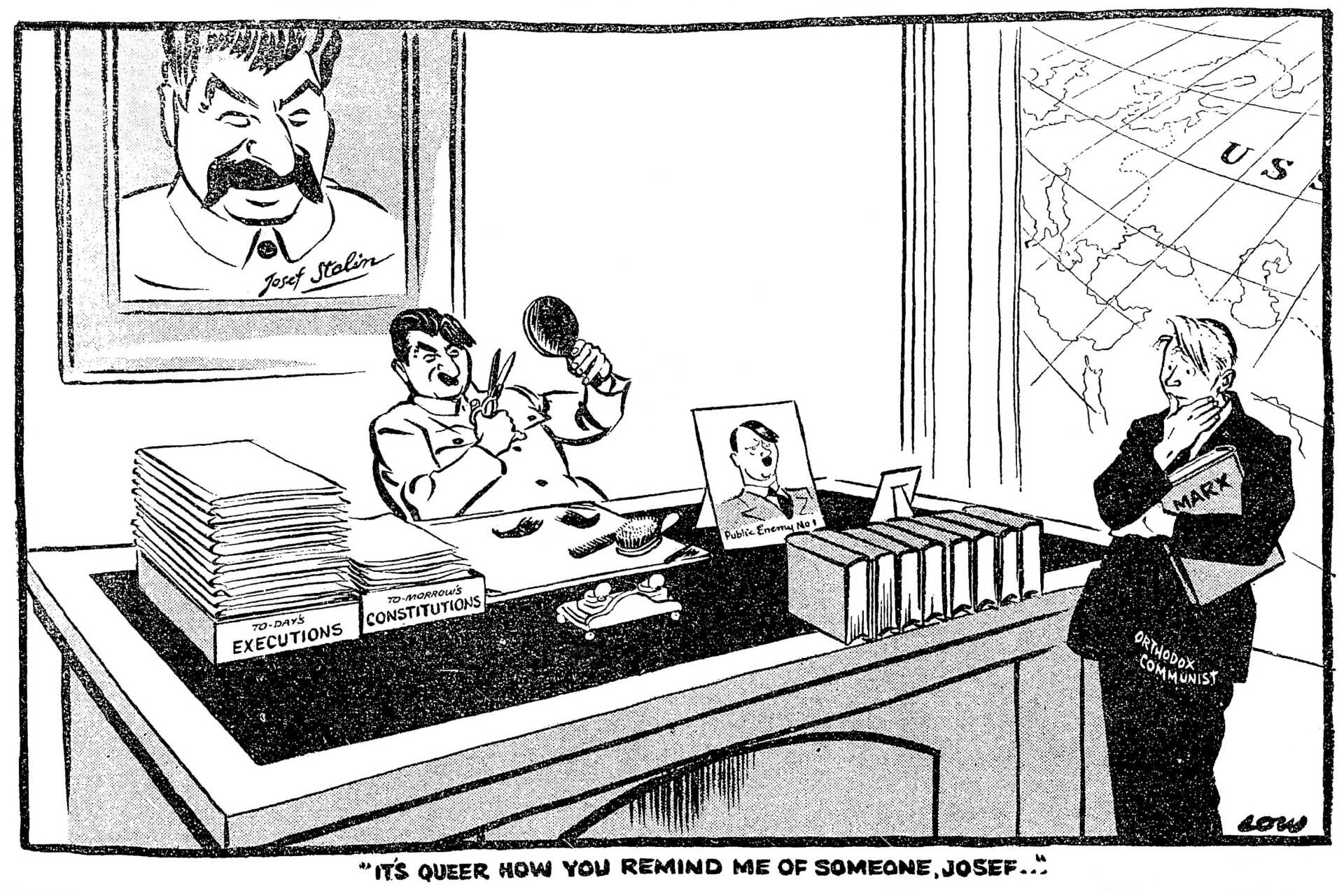

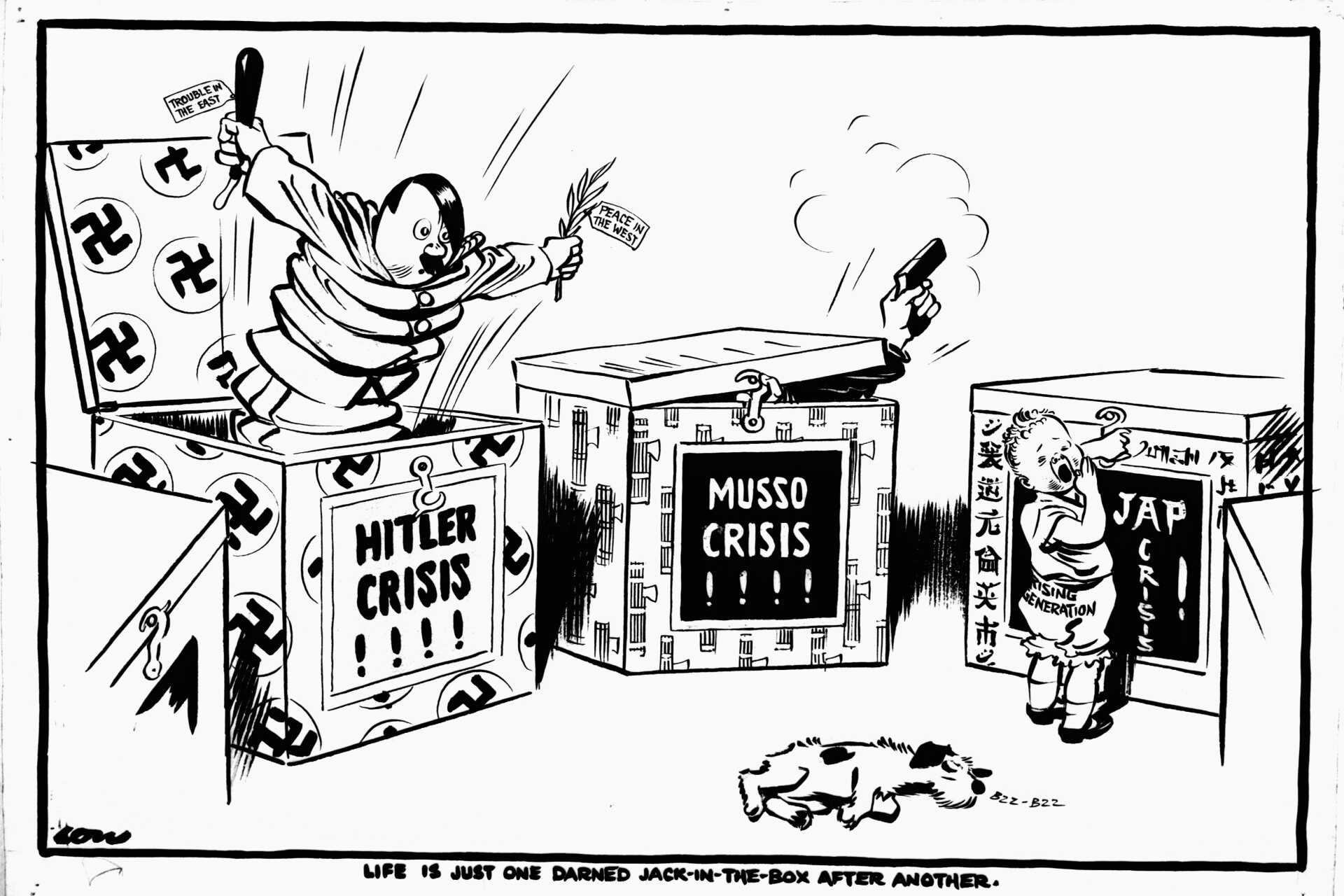

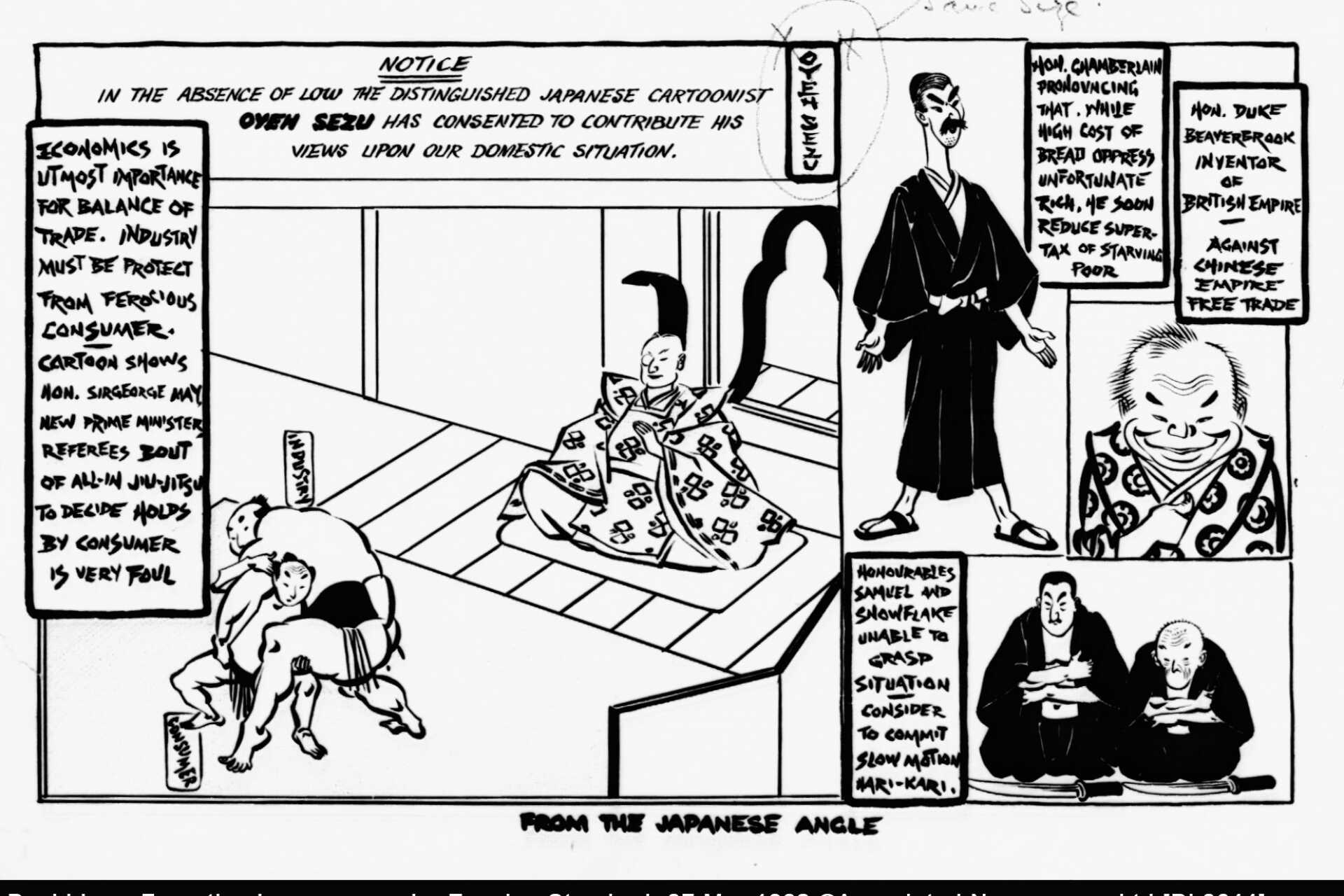

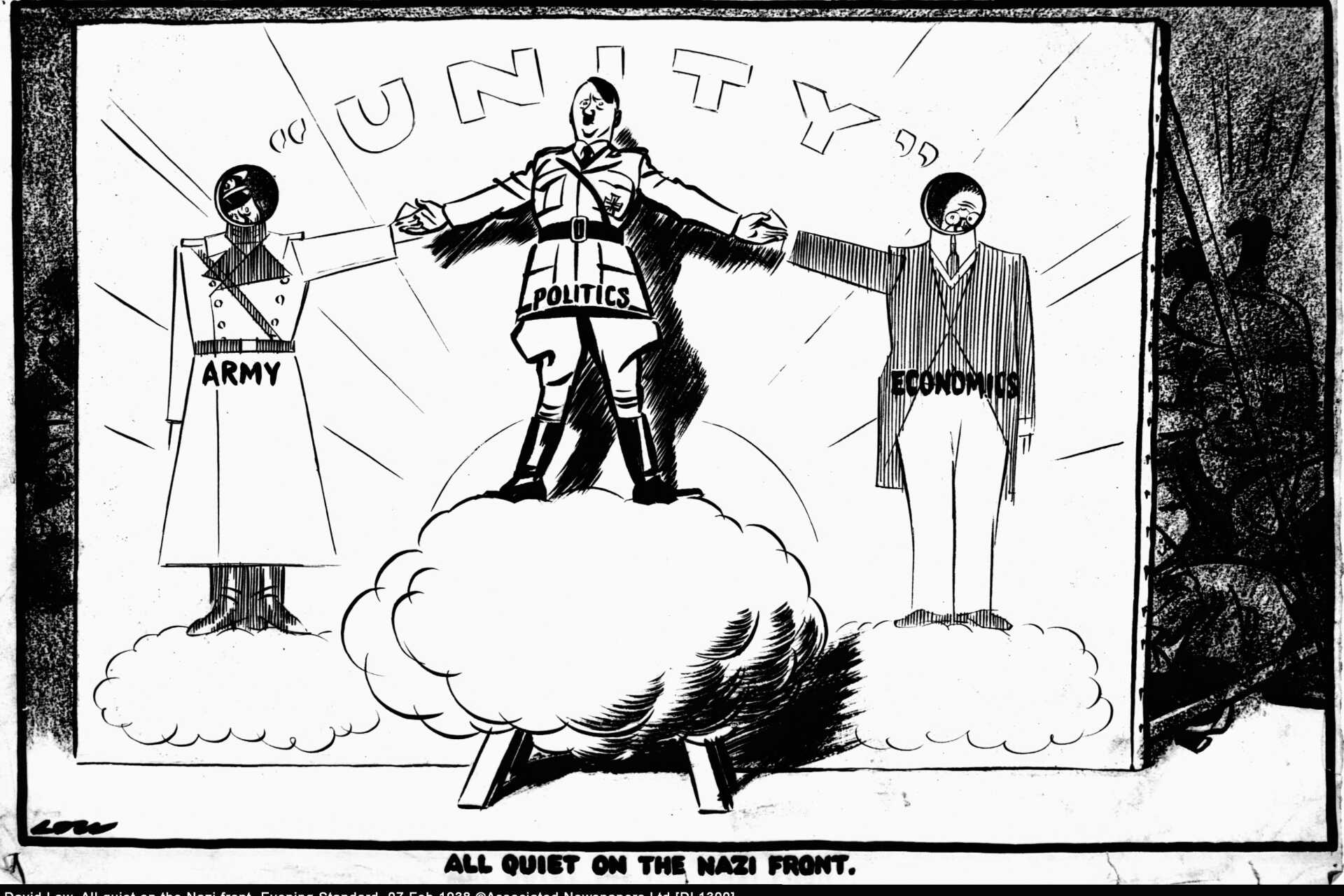

In Britain during the interwar years, the cartoonist Sir David Low (1891-1963) became known for his work in British newspapers, particularly the Evening Standard. Low wielded ridicule as a weapon against the rise of fascism and authoritarian leaders, such as Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini. His illustrations offer a critique of totalitarian ideologies through attractive visuals and witty humour, demonstrating the ways in which cartoons can be used as effective tools of resistance through the power of laughing at an opponent.

The following exhibition explores the importance of cartoons in translating complex political events into easily accessible images, with focus on the cartoons created by David Low, which are an important part of the Beaverbrook Foundation Collection at the University of Kent’s British Cartoon Archives. Through humour, Low successfully created a visual discourse that invited viewers to bond over shared frustrations, encourage critical thinking, and participate in the political arena.

Inflaming Tempers: From One Artist to Another

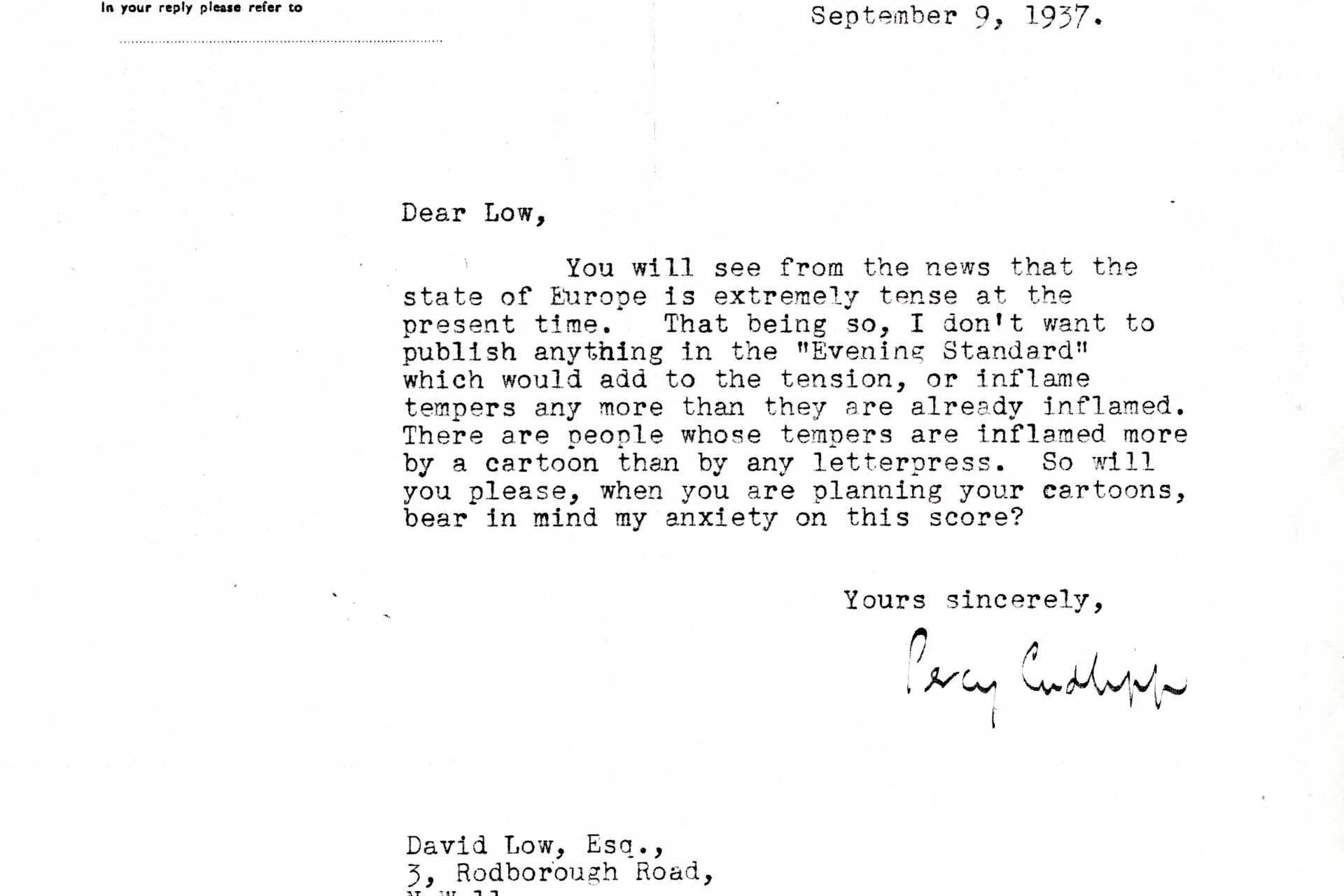

The image on the left is a letter from Percy Cudlipp, editor to the Evening Standard, to David Low, details Cudlipp’s anxieties over upsetting tempers which are triggered “more by a cartoon than by any letterpress.” In November 1936, he wrote to Low regarding his depictions of dictators by stating that “a succession of such cartoons at this time might very well do serious harm.” How could a simple cartoon be powerful enough to upset the state of Europe?

Hitler is well known for being twice rejected by the Academy of Fine Arts in

Vienna; less known is Hitler’s love for cartoons, in which he amassed a

collection and requested originals from artists, including Low. However,

Hitler’s admiration for Low dissipated into anger at the way he was being

represented, resulting in the Nazis applying pressure on the British government

to restrain Low from depicting Hitler in his cartoons. This only increased

Low’s reputation and, fortified with the knowledge that his cartoons were

hitting their target where it hurts, Low continued his assault. Michael Foot,

acting editor of the Evening

Standard from 1938, commented that Low

“changed the atmosphere in the way people saw Hitler.”

Depicting Dictators: Mockery or Menace?

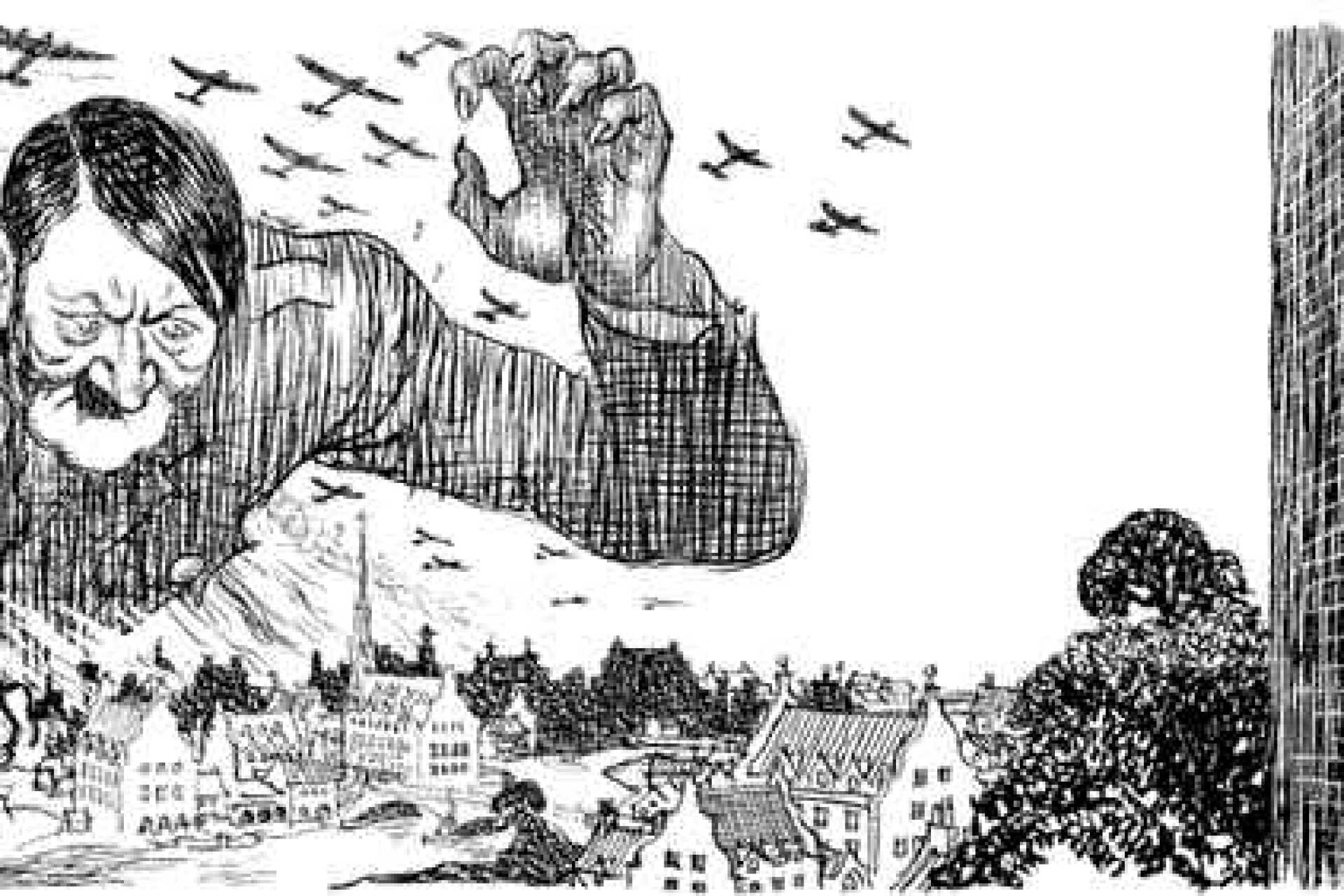

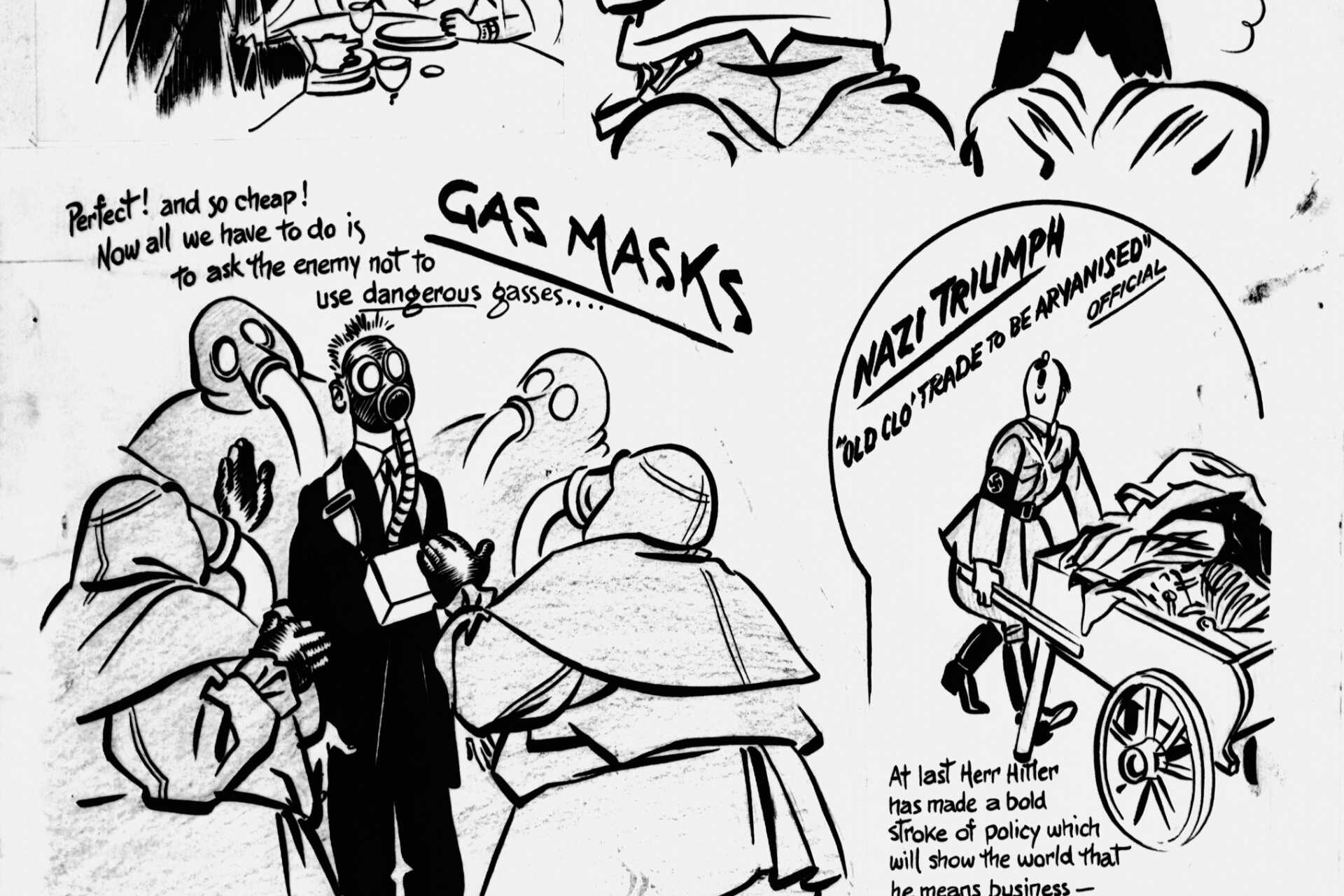

David Low carefully considered his approach to depicting dictators. He grappled with the ways he was able to ridicule authoritarian figures without trivialising the threat they posed to the peace and stability of Europe. Low mentions looking at anti-Nazi cartoons from Denmark and remarked on their representations of Nazi leaders as “dreadful powerful brutes,” which he felt only contributed to the idea of the Nazi Party being “too powerful to resist.” Reflecting on his own cartoons, Low comments that: “the cartoons of mine that got under their skins most were those which made them look like damned fools…” and Low took some personal pleasure when his cartoons were banned in Germany.

Low was, however, very much aware of this delicate balance he needed to strike. On the one hand, reducing dictators to mere buffoons could lead the public to dismiss them as ineffectual clowns and thereby underestimating the growing threat; on the other hand, portraying them as all-powerful risked engendering fear and a demoralised public. Low’s challenge was to create cartoons that undermined the self-importance and pomp of dictators while simultaneously making clear the nature of their ideologies and ambitions.

Some American cartoonists draw H. [Hitler] and M. [Mussolini] as monsters of brutality eight feet high with big hairy arms covered with whiskers, hands dripping with blood, etc., I’m sure no one is more pleased at this than H. and M. themselves, for that is just the effect they have always striven, with all the arts of propaganda, to create among people just before they go out to defeat them.

David Low, 1942

Visual Responses to Fascism: Images across America and Europe

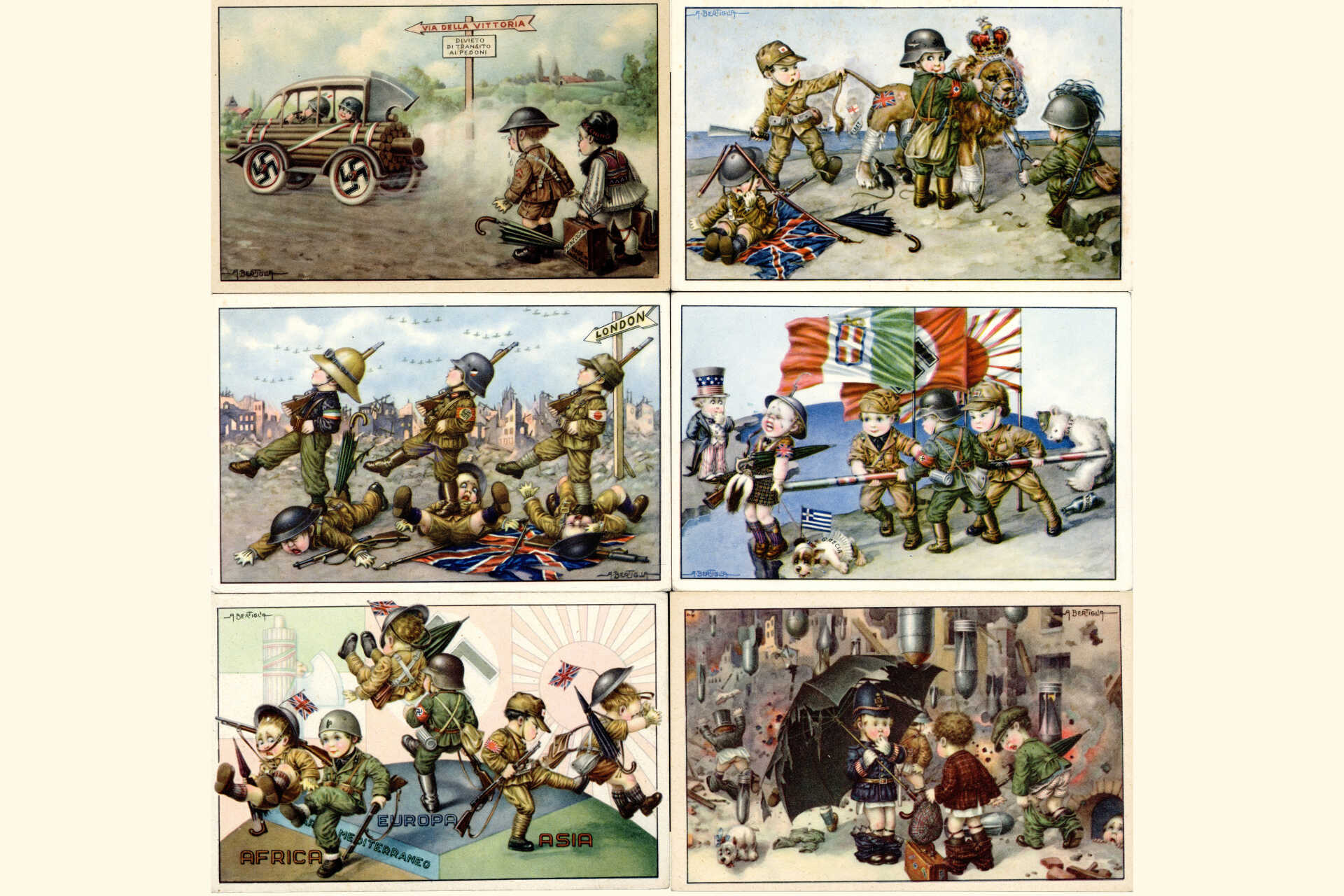

In response to the rise of fascism, a diverse array of visual material, such as propaganda art, postcards, and news publications, was created from both supporters and opponents of authoritarian regimes. These images were significant in shaping public consciousness, influencing perceptions, and mobilising the masses on both sides of the ideological divide across Europe and America.

For those in support, sympathisers adopted visual strategies designed to project strength and unity. Images frequently depicted rallies and military parades, crowds with staged salutes, and leaders in uniforms or heroic postures. These images aimed to appeal to nationalist sentiments and instil a sense of order, belonging, and identity among followers. For those against, anti-fascist images adopted a different visual strategy that focussed on scenes of violence, brutality, and oppression. These depictions were contrasted sharply with the heroic depictions that came to represent the iconography of European fascism and aimed to provoke a sense of outrage as well as inspire resistance.

These outpouring of responses influenced the visual and cultural landscape of Europe and America, reflecting the ways in which images were an important vehicle in provoking or persuading viewers. These visuals highlight the aesthetic and rhetorical strategies deployed by opposing ideologies through their use of emotionally charged iconography that shaped opinion and encouraged political engagement.

Wall of Resistance

This gallery showcases the role of political cartoons as effective tools of resistance by ridiculing leaders and ideologies. As you view these examples, consider the ways in which humour is used. To what extent do you think the cartoons succeed in deflating the aura of power and puncturing the notion of invincibility surrounding those depicted? Consider: Is this funny to you? … or dangerous? … or offensive? Does it make you laugh or does it make you uncomfortable?

John Heartfield

Photomontage Against Nazism

The German artist John Heartfield was famous for his photomontage, a medium through which he took aim at the Nazi regime. His visual criticisms were published in the Arbeiter-Illustrierte Zeitung (the Workers Pictorial Newspaper), where Heartfield connected Hitler’s success with wealthy industrialists, arguing that political authority is fundamentally rooted in economic power.

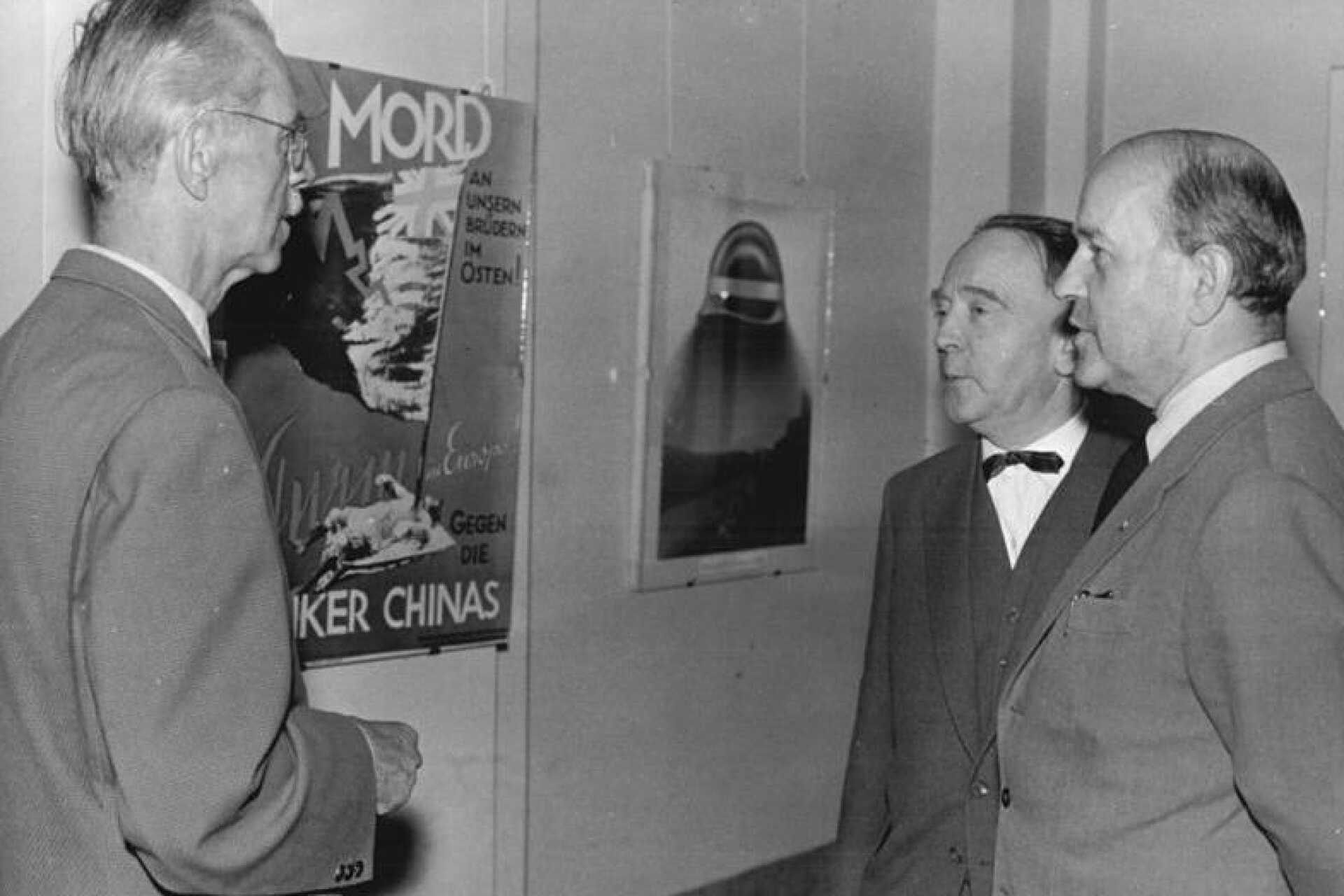

Image: At the German Academy of Arts in 1960, Academy President Otto Nagel (left) in conversation with John Heartfield (second from left) and Wieland Herzfelde about a photomontage by Heartfield.