Early life

Hewlett Johnson was born in Kersal in Manchester on 25th of January, 1874, the third son of Charles Johnson, wire manufacturer, and his wife Rosa, daughter of the Reverend Alfred Hewlett. He had two sisters.

After Macclesfield Grammar School he went to Owens College, Manchester in 1890, where he graduated with a B.Sc. in Civil Engineering in 1894. He won the geological prize and became an associate member of the Institute of Civil Engineers in 1898. However while he was training as a mechanical engineer at the Ashbury Carriage works in Manchester two workmates introduced him to Socialism. In 1902 he married Mary Taylor, who came from a wealthy Manchester family. Her father Frederick Taylor was a merchant from Broughton Park Manchester.

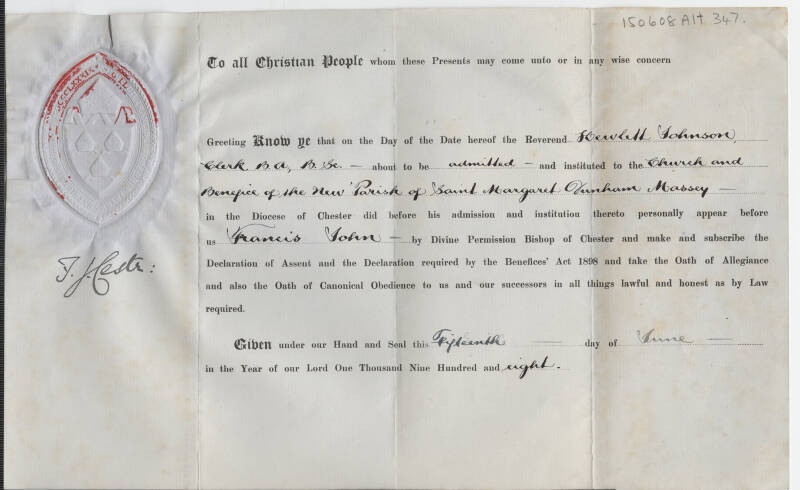

Intending to join the Church Missionary Society he took the first year of the Ordination course at Wycliffe Hall, Oxford, but later studied Theology at Wadham College, graduating in 1905. Hewlett and Mary had both intended to do missionary work but found that Johnson's views of Christianity were not acceptable to the Church Missionary Society. Instead Hewlett decided to go into the church and was ordained deacon in 1905, accepting a curacy at St. Margaret's, Dunham Massey, Altrincham. A year later he was ordained priest, and in 1908 made vicar at the same church.

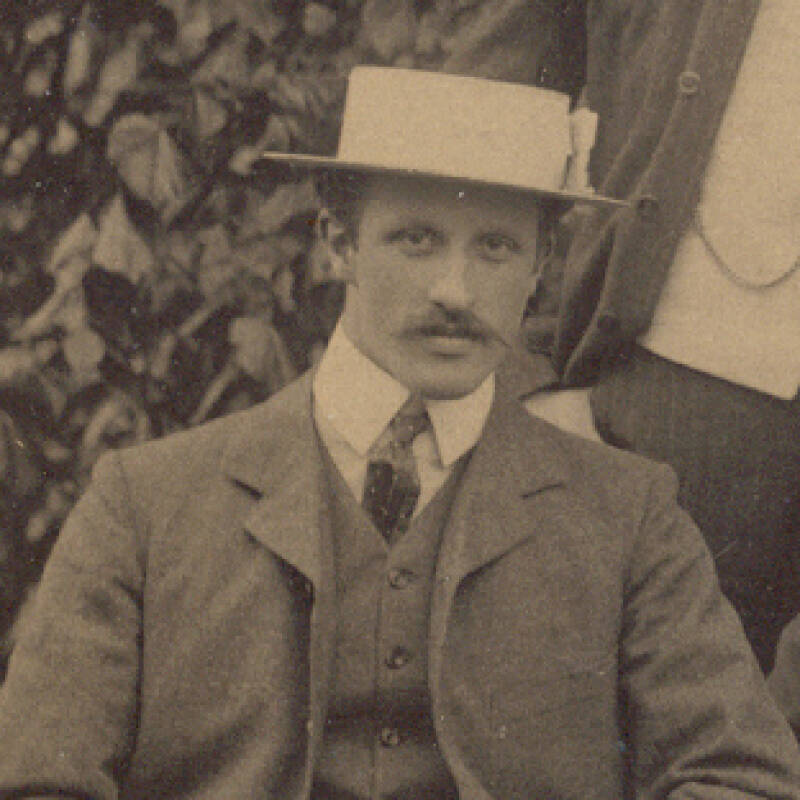

Black and white photograph of a young Hewlett Johnson (undated)

Early clerical career

Johnson quickly became known for his outspoken and liberal, not to mention, radical views, but his ability and hard work in the parish made him a popular figure. Despite the fact that his church was surrounded by the large houses of the wealthy industrialists of of the area, he was concerned for the welfare of his poorer parishioners. He and Mary organised holiday camps in North Wales for children in the Altrincham area,a ground-breaking idea in those days. He also risked the displeasure of his wealthier parishioners by campaigning for the improvement of their workers' housing. Mary ran a Hospital at Haigh Lawn in his parish for servicemen wounded in the First World War, and Hewlett was chaplain to a German P.O.W. camp. His experiences of the impact of war on both countries (he and Mary visited Germany and Austria just after 1918) led to him becoming a pacifist as well as a socialist.

There was also an intellectual side to Hewlett Johnson. He had begun publishing and editing the journal The Interpreter in 1905. This encouraged biblical criticism and promoted biblical scholarship and archaeology. In the twenty years of its publication it attracted contributions from many important theologians and scholars. Hewlett continued studying theology gaining a Bachelor of Divinity degree in 1917, and a doctorate for his thesis on the Acts of the Apostles 7 years later.

Advancement in the Church also followed, and after becoming an honorary canon at Chester Cathedral in 1919, and the rural dean of Bowden in 1922, he was created Dean of Manchester Cathedral in 1924 by the first Labour Prime Minister, Ramsay MacDonald, another pacifist. Now he had more opportunities to promote the well-being of the working classes of the North West. He encouraged children to come to the Cathedral, and by keeping the great doors at the West end of the building open all day made services more visible to those just passing by.

No longer able to sustain the Interpreter, with his increased workload, it ceased publication, but Hewlett began to write for various Manchester Newspapers campaigning for better working class housing and cleaner air. More travelling on the Continent with Mary seeing the cleanliness of Copenhagen and Mussolini's new motor roads in Italy gave him ammunition for his crusades for cleaner air, and against the insanitary, manure-strewn streets of the North West. However despite his time in Manchester being "the one job" he wanted, on the personal front tragedy followed with the death of Mary Johnson from cancer at the beginning of 1931.

The Archbishop of Manchester had been until two years previously William Temple (a member of the Labour Party), then advanced to the Diocese of York. Impressed by Johnson's work and commitment to social concerns he supported Cosmo Gordon Lang the Archbishop of Canterbury in recommending his appointment as Dean of Canterbury. The previous Dean H.R.L. Sheppard, a populist romantic figure, to whom congregations had flocked had been forced to resign after only 18 months in the job, due to ill- health.

Document declaring Hewlett Johnson's admission into St. Margaret's, Dunham Massey, Altrincham, 1908

Dean of Canterbury

In comparison, after Hewlett Johnson was installed as Dean of Canterbury Cathedral, on June 12th 1931, he held the post until 1963, only resigning at the age of 89. Hewlett was now responsible for the services, music, finance, and maintenance of the building of the greatest Church of the Anglican faith. As part of his duties he was also Chairman of the Board of Governors of the King's School, the public school partly within the precincts of the Cathedral. Of course there were other people in the organisation in charge of the army of workmen (e.g. stone masons and glaziers), in charge of the Choir School, and of collecting rents from the Cathedral's tenants, but ultimately the Dean was at the head of the organisation.

Over the years despite frequent arguments within the Cathedral Chapter, Hewlett instigated changes and improvements to the worship and running of the church, using his practical and engineering abilities. Even those who deplored his political views could not lay the charge of dereliction of his duties at his door. Despite his new responsibilities he continued to be interested in industrial conditions and was outspoken in his feelings that the Government should do more to ease economic inequalities.

Black and white photograph of Hewlett Johnson standing on what appears to be a ship (undated)

China 1932

Hewlett travelled widely throughout his tenure, as early as 1932, visiting China on a fact finding mission. The country had been in a chaotic state since the famine of 1920. Local war lords feuded amongst themselves and bandits roamed the country. There was no effective central government to counter Japanese expansionism in Manchuria in the early 1930s, or to organise famine relief after the floods in August 1931.Hewlett toured the country sending back articles to the Times and the Manchester Guardian. He met members of the China International Famine Relief Commission (C.I.F.R.C), visited refugee camps in Nanking, and with Major Todd, the chief engineer of C.I.F.R.C. embarked on dangerous journeys to Mongolia and Tibet inspecting the roads he was building. This led to a great love of the country itself,and to admiration for the small selfless band of communists also aiming like him to ameliorate the conditions of the people, but at that time persecuted for their beliefs.. Hewlett can be seen, in the photos of the period visiting road projects and makeshift tented villages. His reports back to the Western press made him a star, "for the dangers he had passed", rather than getting over the message he wanted to convey.

Canterbury

At home back in Canterbury Hewlett found life rather tame, after China and even bustling Manchester. It was difficult for a Northerner moving into an established complex organisation, which had functioned quite well during his absence. Normally totally involved with everything he did, he found himself frustrated, bored and lonely without Mary. At this point he threw himself into involvement with the arts. The Friends of Canterbury Cathedral had commissioned T.S. Eliot to write a drama for the 1935 Canterbury Festival- "Murder in the Cathedral". Also for the Festival Sybil Thorndike gave a lecture on drama, and she and her husband Lewis Casson became friends. However Hewlett also continued his interest in politics, attending Workers' Educational Association lectures, where he met the man later to become one of his greatest friends, A(Alfred) T. Dye, who lectured in history, politics and economics. Meeting Ivan Maisky, the Russian Ambassador he invited him to stay at the Deanery, and the two men became friends- a friendship that was frowned on by the Church.

The visit of Gandhi to the Deanery in 1931 had already caused consternation in the Anglican Establishment, as did Hewlett's service of Evensong for the Salvation Army under General Higgins. It was also about this time that Hewlett met his cousin's daughter, Nowell Edwards, then a student of art at the Royal College in London, and she became a frequent visitor to the Deanery. In 1938 they announced their engagement before embarking on a holiday in Spain, still Republican but about to be taken over by Franco and the Nationalists. They were married, by Nowell's brother Stephen at his church in Stokesay, Shropshire in a quiet ceremony in the autumn of that year.

Photograph showing Hewlett Johnson with Mahatma Gandhi during Gandhi's visit to Canterbury, 1931

Spain, Canada and Russia

Hewlett had already visited Spain during the Civil War in March 1937, as a member of a religious delegation at the invitation of the Republicans, witnessing an attack on the town of Durango by German planes. He returned to a rebuke from the Archbishop of Canterbury Cosmo Gordon Lang with whom he had bee confused by the Spanish media. He had already publicly backed and spoken, in Canada in support of the Social Credit scheme of C.H. Douglas as a means of combating the Depression, but attempts to put the theory into practice had failed.

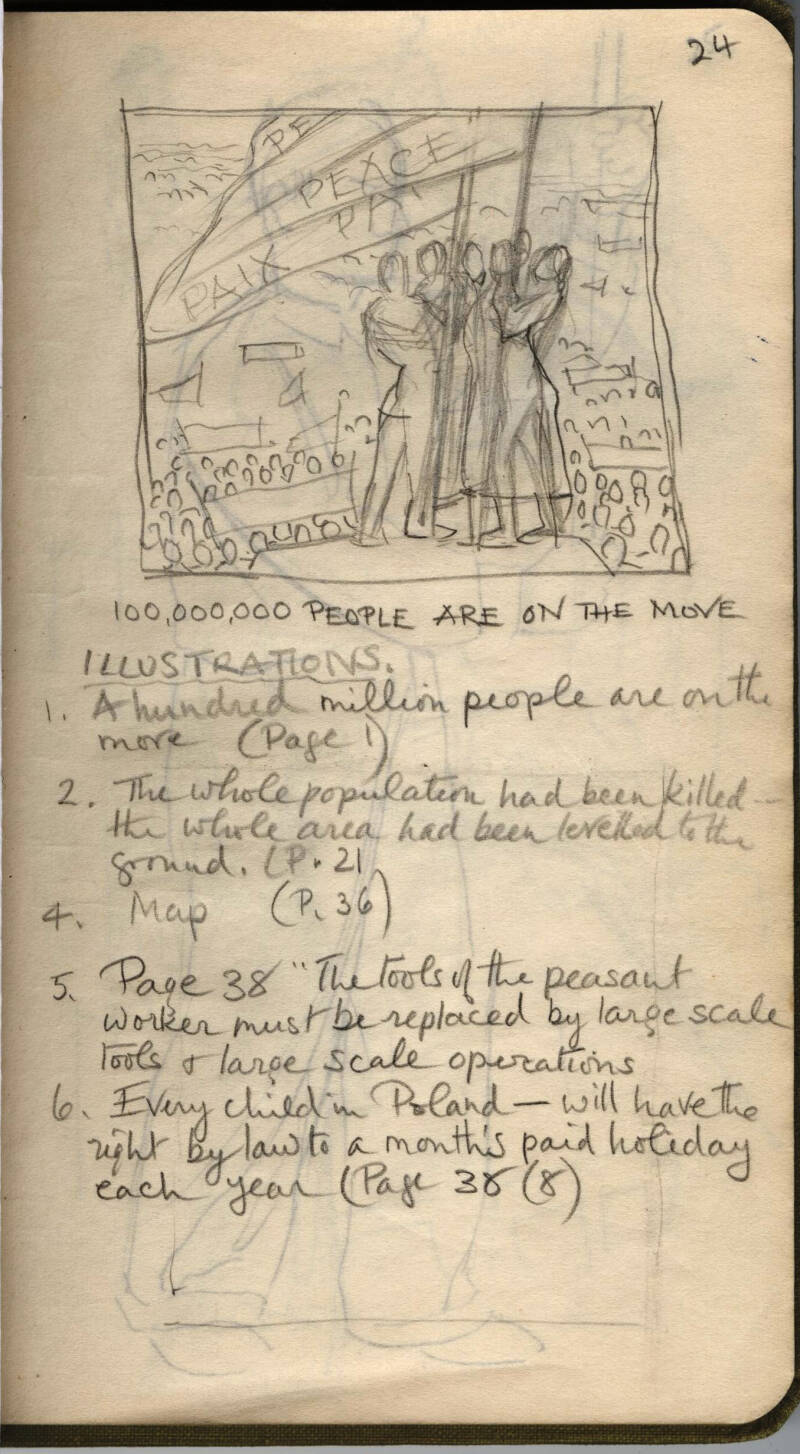

In the intellectual struggle against Fascism Hewlett had been drawn into the circle of the Left Book Club, many of whose members saw the solution as a move towards Marxism. Nowell had already toured Russia in 1936, A.T. D'Eye had visited in 1934, but it was not until 1937 that Hewlett spent 3 months there. When he returned Victor Gollancz, the founder of the Left Book Club asked him to write a book to explain to British people Russian Communism. This proved to be a collaborative effort as Hewlett was helped in the writing by D'Eye and by Nowell who did the illustrations. Before publication of the book in March, 1939 Hewlett wrote a pamphlet "Act Now! An Appeal to the Mind and Heart of Britain"- published by Gollancz, which contrasted Fascism and Socialism and argued for Russia's solution to the world's problems.

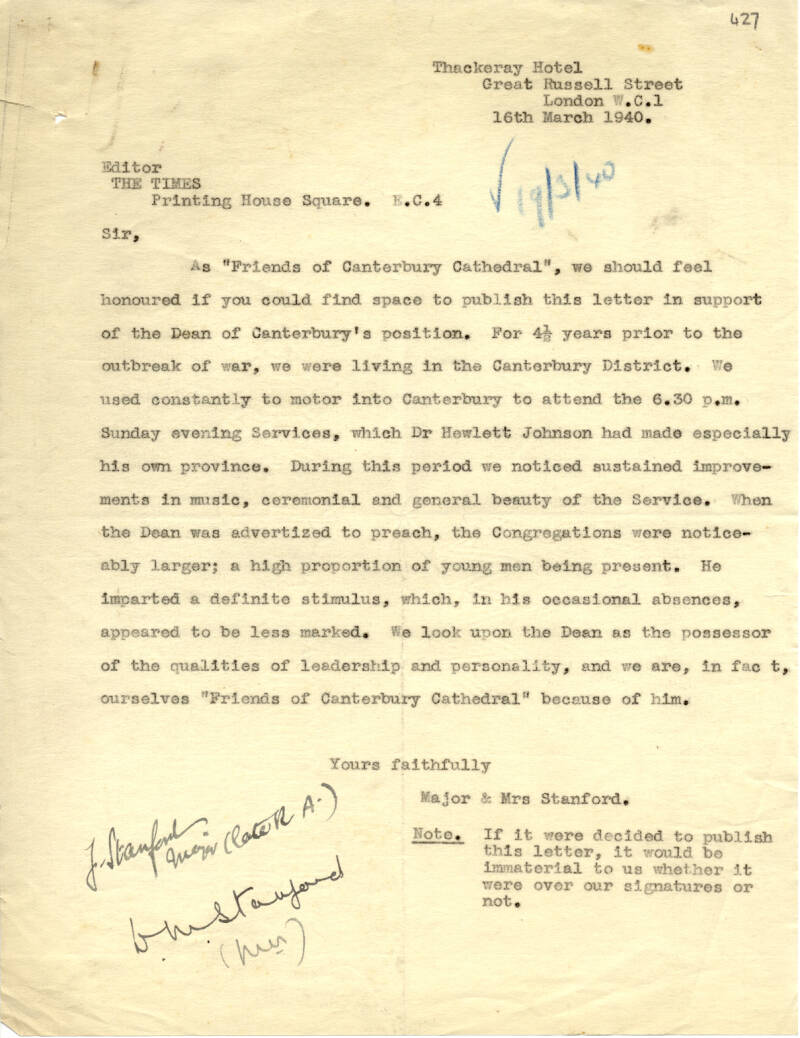

In August with the signing of the non-aggression pact between Russia and Germany relations between him and Gollancz cooled. Later the commissioned book "The Socialist Sixth of the World" was published, but in December, after the declaration of War with Germany on September 3rd. By this time Hewlett had the protection of the Cathedral to occupy his mind.

Letter written in support of Hewlett Johnson, March 1940

World War II

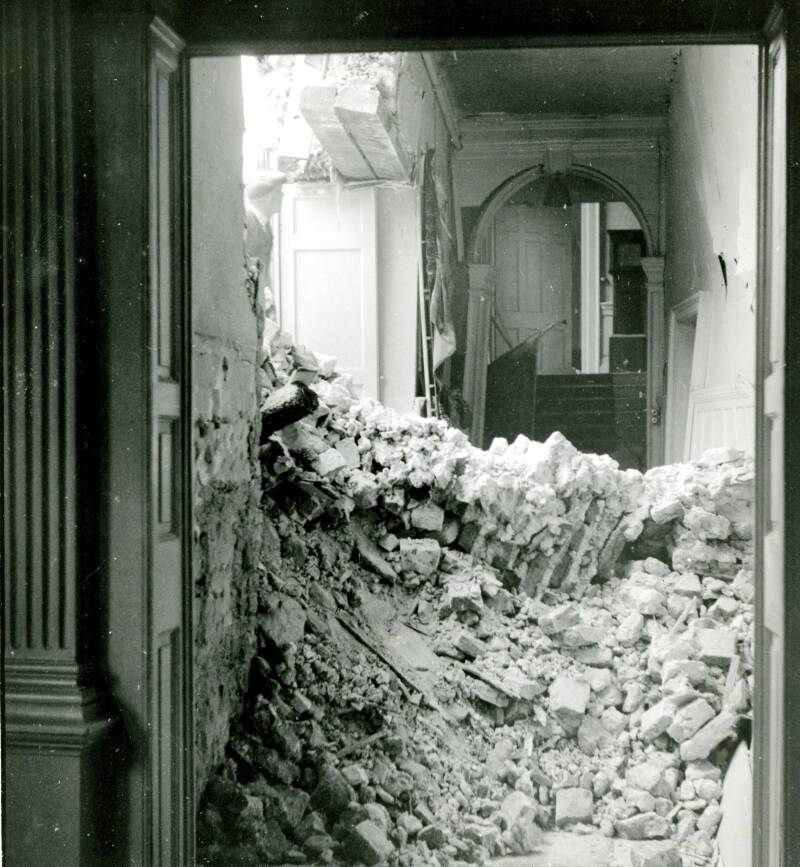

Hewlett's measures to ensure against the destruction of the Cathedral by bombing didn't meet with universal approval, especially during the "phoney war", but the stained glass was removed and a large amount of earth was brought into the building as a cushion to reduce the shock to the building if the roof caved in. The Deanery itself was partially destroyed by a bomb just outside in October 1940. Several other houses in the Precincts were damaged during the war, and their occupants cheerfully put up in the Deanery, by Hewlett.

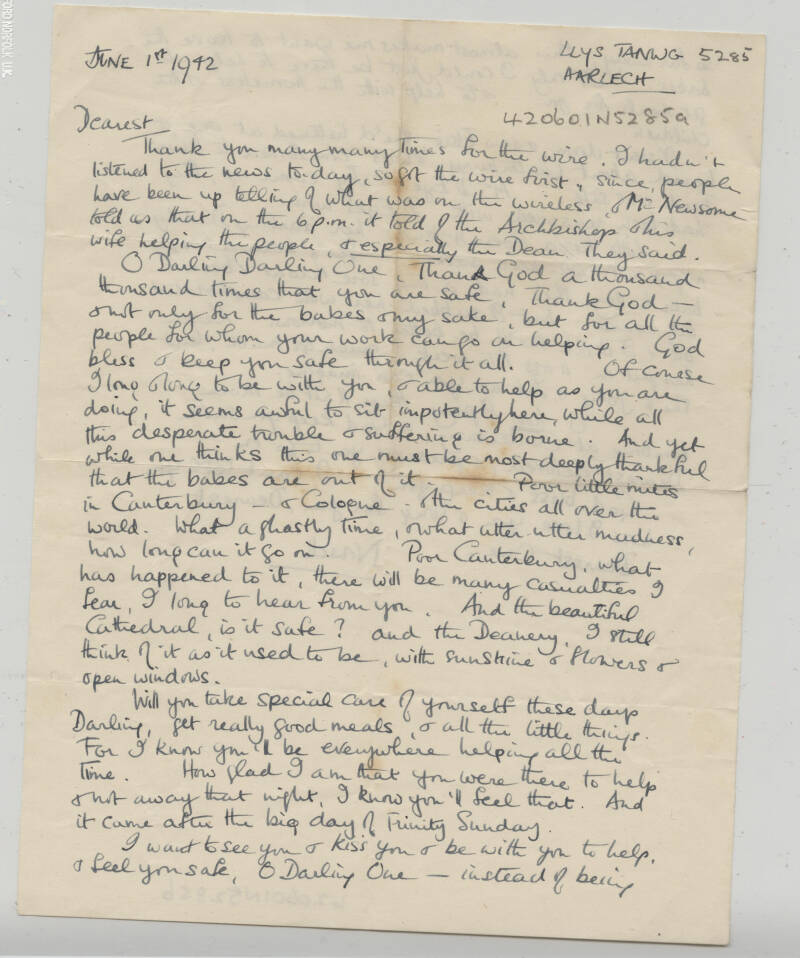

The Dean's own family were safe in a holiday home near Harlech, North Wales. Nowell had given birth to their first daughter Mary Kezia in March 1940 and their second Helene Keren in 1942. They spent the war years away from Canterbury giving shelter to many friends including A.T. D'Eye's daughter Joy. Some of those clerics sheltered by Hewlett in the Deanery were Canons who had signed a letter in The Times in March 1940 disassociating themselves from Hewlett's views in "The Socialist Sixth of the World".

Antagonism towards Hewlett lessened slightly in June 1941 when Hitler invaded Russia, and the military experts were proved wrong in their assertion that Russia would be defeated in a few weeks. Hewlett and D'Eye had confidently predicted that this was a move too far, and in September 1941 Hewlett had a visit from General Montgomery, anxious to learn all he could about Soviet strengths, from the Dean- and his book- a copy of which he took away. Then in 1942 Cosmo Lang was replaced by Hewlett's old champion William Temple as Archbishop of Canterbury.

However the bombing attacks on Canterbury reached a new height of destruction on May 31st 1942 when the Cathedral was only saved from fire by the work of the firemen and wardens' work in disposing of incendiary bombs falling on the roof. The town itself was also badly hit, and Hewlett was busy distributing food to families whose homes were now shells.

Photograph showing bomb damage to the inside of the Deanery, 1940

Victory in Europe

At the end of the war Anglo-Soviet aid groups and cultural groups sprang up all over the country. Hewlett and D'Eye set off for U.S.S.R. on a fact finding tour in April and were there at the same time as Mrs. Churchill in her position as the president of the British "Aid to Russia" fund. On May 9th Hewlett and D'Eye were at the Russian V.E. Day celebrations in Moscow. According to the Times 'Workers formed circles and sang while traditional Moscow dances were performed. Factory girls swept down the streets with arms linked. Students gathered outside the hotels where diplomatists and foreign visitors were staying. A short while ago they were carrying shoulder high the Dean of Canterbury.' (The Times, May 11, 1945; pg. 4; Issue 50139; col D, Victory Day In Moscow A Vast Panorama, Salute From 1,000 Guns, From Our Own Correspondent)

During his ten weeks away from Canterbury the Dean visited Poland, and many parts of the U.S.S.R. including Leningrad, Samarkand and Tashkent. He was summoned to the Kremlin to meet Stalin on the 6th July, awarded the "Order of the Red Banner of Labour" by the praesidium of the Supreme Soviet on the 13th and had already been presented by Patriarch Alexei with the pectoral cross he would, controversially wear for the rest of his life.

America, November 1945 and 1948

Before too long the Dean was asked to visit the opposing side in the Cold War which was imminent. He was asked to the U.S.A. by members of the National Council for American-Soviet Friendship in particular to speak at a rally at Madison Square Garden. In the course of his visit he met Joseph Davies, the American ambassador to the U.S.S.R, La Guardia, Mayor of New York, President Truman, Henry Wallace, former Vice-President, Dean Acheson, Corliss Lamont and Paul Robeson.

Despite rumblings at home about the extent to which he was implying that he was acting as a representative of the Anglican Establishment abroad, and not as a private individual, and even though his first application for a Visa was refused, Hewlett was off again to the U.S.A. in 1948. He toured Canada and the Mid-West as well as the Eastern sea-board and again spoke triumphantly at Madison Square Garden.

Although berated by letters from the new Archbishop of Canterbury, Dr. Fisher, implying that he must choose between his support for one particular political view, and his position as Dean, Johnson carried on as before, visiting the World Congress of Intellectuals at Wroclaw, Poland in 1948 and the World Peace Council Meeting in Paris in 1949 where scientist Pierre Joliot-Curie, artist Pablo Picasso and singer Paul Robeson were all delegates.. In February of 1949 he had given evidence with officials of the U.S.S.R. against Victor Kravchenko who had exposed some of the less attractive sides of Communism in his book I Chose Freedom, after defecting to the West.

Page from Nowell's travel diary during the Johnsons' visit to Hungary in 1951

Frequent "Fellow Traveller"- at 76

On 11th April 1950 Hewlett set out on his longest journey yet, to Australia via Rome, Karachi, Calcutta, arriving in Melbourne via Sydney and Darwin on 15th.He spoke to various Peace Rallies, to various groups- trade-unionists, miners, railway-men, dockers and students in a variety of locations, meeting up with other peace campaigners like the Americans, Fred Stover of the Iowa Farmers Union and Professor Fletcher of the Episcopal College, Harvard. His tour was arranged by Mrs. Jessie Street, the wife of Australia's Chief Justice. When about to leave for his next speaking engagement in New Zealand it was discovered that the U.S.A. had refused the visa needed to pass through Honolulu on his way home from Auckland via Vancouver. Undaunted he returned to England via Sigapore, Bombay, Karachi, Cairo and Rome (where he enjoyed a drive round the city), arriving after 3 days travelling to the welcome of Nowell and the children- only to set off again for Toronto on 6th May. While in Canada he visited Ottawa, Port Arthur, Calgary and actually found time for a day's holiday, at Niagara.

There was a massive Peace Conference in Czechoslovakia in June, and again Hewlett was to be guest speaker, visiting Devín and Velerhad between 29th and 7th July. However the situation at home, over his political views had worsened. He was ostracised by the rest of the clergy, some of whom were bent on forcing his resignation. On the day before he left for Czechoslovakia he had recorded in his diary that he and Nowell discussed what to do if he was "removed". Also the world situation was in a volatile state. The next day the Korean War broke out between the Communist North and the U.S. backed South Korea.

Despite these uncertainties even chance conspired to give him the opportunity to travel, when a November 1950 Peace Conference in Sheffield was moved to Warsaw, as some delegates were refused visas to travel to the U.K. He spoke there despite a cold; the next year in January, despite an attack of Shingles he spoke at the World Peace Conference in Berlin. He was to be rewarded for his efforts- although in what the West would see in a dubious light.

Photograph of Hewlett posing amongst crowds of people welcoming him to Australia, 1950

Stalin Peace Prize

In April 1951 news came that Hewlett had been awarded the Stalin Peace Prize, only the 2nd recipient of the honour which the Eastern bloc thought of as their version of the Nobel Prize. It was presented in June and followed by a reception to which many of his old Russian friends were invited, including Inna Koulavskaya who had acted as guide and interpreter in 1945, Patriarch Alexei whom had given him his Pectoral Cross, and Nikita Khrushchev, whose congratulatory letter to him can be seen in the Diploma case.

Photograph of Hewlett and Nowell receiving flowers during the ceremony where Hewlett was awarded the Stalin Peace Prize, 1951

Hungary, Roumania, Bulgaria, 1951

Hewlett and Nowell's Summer holiday that year gave the opportunity to see some of the Eastern bloc countries, and to assess the relations between the churches and the state. They visited Hungary, Roumania and Bulgaria looking at holiday camps for children and workers on the Black Sea, saw processions on August 23rd to commemorate Roumania's National Day and compared the hostility between the Roman Catholic Chruch and the Hungarian authorities, to the fairly harmonious existence of Orthodox Christianity and the government of Roumania.

Photograph of Hewlett holding a young child during an international visit

China, 1952 and the aftermath

In 1952 came the Johnsons' first of three visits to China as a couple. Since Hewlett's exciting trip in 1932 much had changed- the People's Republic, under Mao Tse Tung had been formed three years previously. A. T. D'Eye joined them in this 7 week journey and shared the platforms with Hewlett and Nowell. They met Chinese Christians like Bishop Ting, statesmen-Mao and Chou En-Lai, and the New Zealander Rewi Alley, social reformer and writer.

However whilst there Hewlett was caught up in the Chinese allegations of the American use of Germ Warfare in the Korean War. Returning to England with various documents held to prove this he stepped into a furore which led to him almost being dismissed. Archbishop Fisher signed a motion to that effect in the House of Lords, but Hewlett had his supporters and the motion came to nothing. Public opinion at the time was definitely on the side of the Americans as our allies, despite the McCarthy Witch hunt. Hewlett even had to give evidence at the American Embassy in London in September, 1954, in a case against the National Council of American -Soviet Friendship when the Americans tried to prove that it was run by Communists.

Photograph of Hewlett and Nowell during a visit to China in 1952

Russia 1954

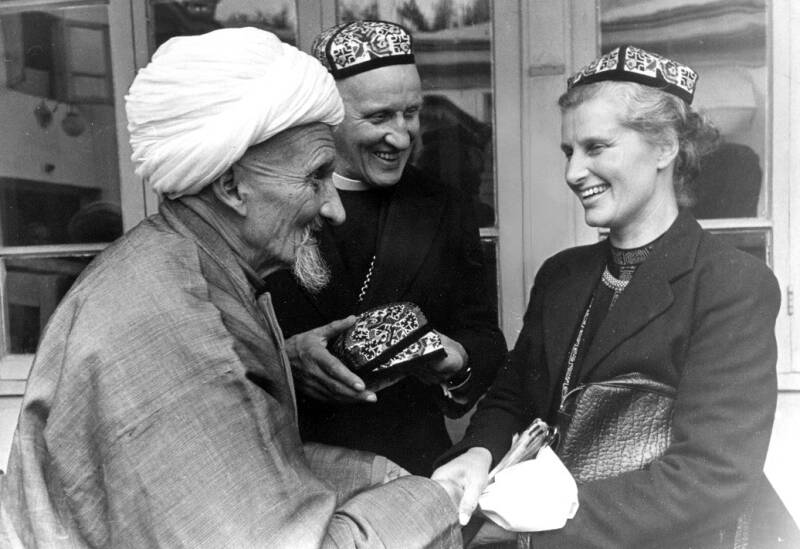

It came as a pleasant break after all this for Hewlett and Nowell to go off on a tour of the U.S.S.R., meeting Patriarch Alexei again and visiting Moscow, Stalinabad in Tajikistan, Alma-Ata in Kazakhstan and Tashkent in Uzbekistan. Despite the fact that Hewlett was now 80 they toured agricultural shows, factories, and mosques meeting an even more elderly cleric, the Imam of Tashkent.

At home their relations with the Anglican establishment were no better. In 1956 a row sprang up between the Archbishop of Canterbury and Hewlett over the visit of the former premier of the Soviet Union, Malenkov. Hewlett ended an acrimonious exchange of letters by pointing out that as Malenkov had also visited Westminster Abbey and St. Pauls, his own hospitality at Canterbury had not been inappropriate.

Hewlett Johnson also travelled in Europe and in Russia and China and came to be a strong advocate of the socialist and communist systems. He maintained his views on the Soviet achievement despite any evidence produced to the contrary. His political interests journeys, speeches and writings all held him in the public eye and he gained the nickname of 'the Red Dean' and became a source of great embarrassment to both his fellow churchmen and the political establishment.

Photograph of Hewlett and Nowell meeting an imam in Russia, 1954

Russia and China en famille, 1956

With the idea of writing a new book on China, Hewlett decided on a long Summer tour of the more remote areas of the U.S.S.R , and China itself. This time the two girls, Kezia and Keren, would go with them. It was felt that a doctor needed to be included in the trip for Hewlett's benefit as he was now 82. However the gruelling "holiday" turned out to affect the girls and Nowell, rather than their father. Many late nights of banquets and speeches, early morning flights and lack of sleep meant that more often than not Nowell, in her diary, writes "Kezia unwell", "Keren unwell".

One of the places they visited again was Alma-Ata where they looked at an electric power station, a collective farm and an observatory, as well as receiving hospitality from ordinary people in their homes. After an 8 hour overnight journey by car and plane they arrived in Urumchi in China where the two girls were found to have temperatures of over 100F and told to rest for 2 days. From they went on to Kiu Chang, their base for a two day visit to the Tun-huang Caves where Nowell indulged her love of art. From here on 31st August to Lanchow, where they met Rewi Alley again, visited his school and did some shopping. On 5th September they visited the Kumbum Monastery, where they met 7 and 10 year old "Living Buddhas". Between 13th and the 19th September they were at Kunming, and saw the "Rocky Forrest". Then on to the Yangtze River where they spent 3 days on a steamer going through the Gorges, before boarding a train to Peking. From here they made an excursion to the Great Wall, and the Ming Tombs, on the 26th September.

Whilst in Peking the Johnsons visited various Christian groups, Nowell went to sit in on criminal trials and Hewlett made a Radio broadcast. However one of the highlights of the visit was Chou-En-Lai's State Wine Party on 30th September, which was attended by Mao Tse Tung and President Sukarno, and the great processions the next day for the celebrations of China's National Day.

Their next destination in early October was Ulan Bator in Mongolia, where Hewlett was presented with the Mongolian Star for his peace campaigning. Finally, after a two day journey, touching down briefly in snowstorms in Siberia, for the odd hour's rest and refreshment, they arrived back in Moscow on October 6th. Three days later, starting at 2.00am they flew back to England via Vilnius, Prague, and Brussels arriving at a hotel in London at 12.00 midnight. Almost immediately the two crises of Suez and the Hungarian Revolution intervened to spoil any post-holiday euphoria the elder Johnsons might be feeling. Their two daughters demanded to go back to school straightaway!

Photograph of Hewlett Johnson meeting people on a visit to China, 1956

1957 onwards

Hewlett's failure to condemn the Soviet Union's invasion of Hungary led to further ostracism within the Cathedral Precincts. The King's School banned all contacts between him and the boys. Undaunted, Nowell, Hewlett and Keren went to Poland in July, and in November the two parents went to the fortieth anniversary celebrations of the October Revolution in Moscow.

The Lambeth Conference in July kept Hewlett in Canterbury in the Summer of 1958; a busy year for them both. Nowell, Hewlett and Keren were all ill in the Spring of 1959 (Hewlett with Double Pneumonia), and the parents both went to recover to a health resort on the Black Sea called Oreanda. This seems to have restored the Dean's robust constitution, and in October the Johnsons visited China again, this time without their 2 daughters. They saw communes, and factories, reservoirs and the Lung-Men Caves at Loyang, met old friends like Bishop Ting and Rewi Alley and were entertained by Chou-en-lai.

Then in November 1960 Hewlett and Nowell travelled to East Germany where the Dean received an honorary degree from Humboldt University, during their 150th anniversary celebrations. In 1961 Hewlett appeared on an ITV programme called "Head On", when he was interviewed by a young Jeremy Thorpe, and managed to hold his own in the exchanges, despite his not knowing the questions beforehand, and his eighty-eight years. At the Royal Albert Hall on March 5th 1961, Hewlett was also presented with an album of photographs to commemorate his association with the Daily Worker newspaper, having been a member of the board and its chairman.

Photograph of Hewlett Johnson with a large pile of books, likely in the Deanery.

Retirement and beyond

The same year Hewlett's old protagonist, archbishop Fisher had retired, and there was something of a rapprochement between the two men. However the atmosphere in the Cathedral precincts was still hostile and following an accident in which he broke his collar-bone, and a final unpleasant incident in the Chapter, Hewlett tendered his resignation in December of 1962- to take effect from the following April.

After a nightmarish move, during which they received no help from the residents of the precincts, and having resorted to a bonfire to rid themselves of some of their long accumulation of paper and gifts from all over the Eastern world, they moved to a house already owned by Hewlett in New Street, Canterbury.

Even then the travels did not stop. At the beginning of 1964 Hewlett and Nowell went to Cuba to take part in the 50th Anniversary of Cuba's independence, at the personal invitation of Fidel Castro. Later, in May, they were off again on another visit to China, involving a two day plane journey to Hong Kong, and then a train to Canton. A doctor was in attendance on Hewlett all through the visit, and he and Nowell had medical tests and two days of hot spa baths in a resort on the Liu Shi Ho river, as well as the obligatory visit to a power station. From Canton they flew in Chou-en-lai's own plane, equipped with oxygen in case Hewlett needed it to Nanchang. Next to Hangchow where they saw a silk factory, the usual communes, kindergartens, films and concerts interspersed with medical tests and treatment for the Dean, who was finding the holiday tiring.

At Peking airport they were met by Chou-en-lai and his wife, and lunched with him the next day, when they were pressed to extend their visit by another fortnight. Again both had lots of medical examinations and tests, and they met their friends Bishop Ting and Rewi Alley again, and also on 21st June, Mao Tse Tung. On their return they spent a few days in Karachi, where they were shocked by the poverty in comparison to China.

Letter from Nowell (living in Aarlech) to Hewlett (in Canterbury), 1942

Death

Hewlett was already 90 when he made his final visit to China. Despite his famous stamina he eventually succumbed to pneumonia on October 22nd, 1966 at the age of 92. Despite the long years of acrimonious relations with the other cathedral clergy he was buried in the Cloister Garth.

Many years have now passed and the U.S.S.R. has broken up into independent states. The Cold War has been replaced by a different conflict with supposedly religious divisions, but to read one of Hewlett's Christmas messages, published in the Daily Worker is to find his statements on the outwardly Christian West quite telling, if his faith in the Communist solution a little naive. One is left with the impression of an essentially good and practical man, blinkered to the faults of the Communist world by his passionate belief in the guiding principle "From each according to his ability, to each according to his need".

Compiled by Sue Crabtree, Special Collections Librarian, 2008