Early Pantomime

In this section we'll explore early versions of pantomime, including Commedia d'ell Arte, as well as taking a look at Joseph Grimaldi, an undisputed star of early pantomime best known for his character of Clown.

Joseph Grimaldi

Born into an acting dynasty in 1788, Joseph Grimaldi’s legacy would far surpass his lineage. His father, Giuseppe, was a dancing master and successful Pantaloon in 18th century pantomime; Joseph – with his red-on-white face paint, litany of comic songs, physical aptitude to tumble, duel and construct satirical costumes from an assortment of curious props – would be forever immortalised as the father of clowns. To this day, professional clowns (otherwise known as ‘Joeys’) flock to Hackney every February for a Grimaldi memorial service, and a statue of Grimaldi can be seen a stone’s throw from Sadler’s Wells Theatre in Joseph Grimaldi park.

Grimaldi launched his clown in a pantomime called Peter Wilkins; or, Harlequin in the flying world, which was performed at Sadler’s Wells in 1800. His character was called ‘Guzzle the drinking clown’ and was paired in a comic double act with another clown, ‘Gobble the eating clown’. There’s something Falstaffian about these characters’ names; and much of the Regency clown’s humour would derive from skulduggery and vulgarity. As such, one could argue that this clown had more in common with Commedia dell’Arte’s Arlecchino than the Harlequin he devolved into. Grimaldi also developed a knack for satirising fashionable society and revealing the baseness that unites humanity despite our preening pretensions to civility.

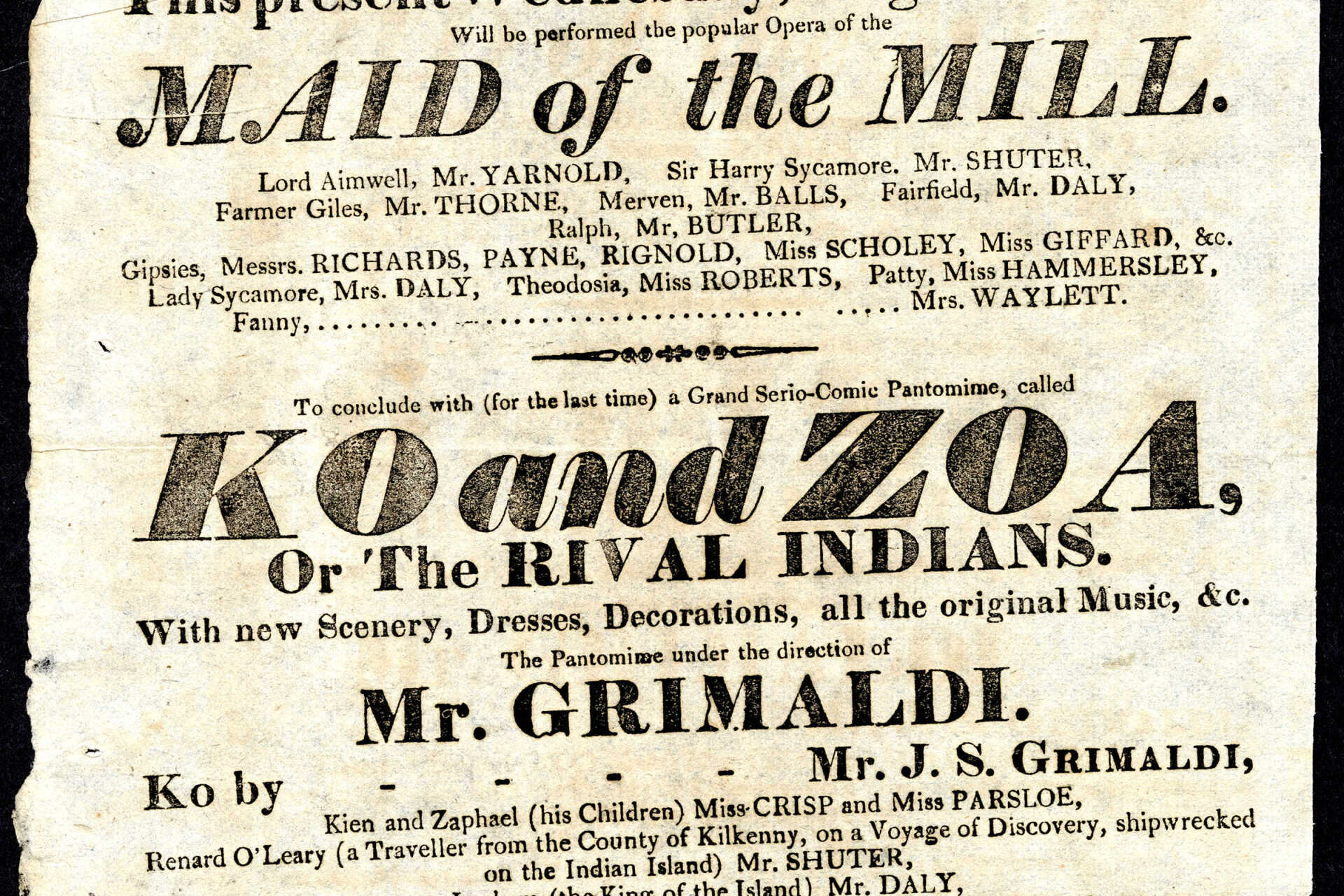

Some of the sketches

and songs he devised in certain pantomimes became so famous that they were

frequently offered as bonus content in an evening of theatrical entertainment.

It is important to note that plays were not performed in isolation at this time;

audiences expected to see a serious headlining drama followed by a burlesque or

pantomime and often additional interludes such as addresses by famous actors or

musical song and dance numbers. Another difference between theatre today and in

the past relates to audience behaviour. Whilst we are accustomed to turning our

phones off in the theatre, and breaking silence only to surreptitiously quaff a

Malteser or chorus, when prompted, ‘He’s behind you’, a Regency-era audience

had a remarkably more informal etiquette – they would come and go, eat, drink

and heckle when they pleased.

Besides his clown persona, Grimaldi was also known for his drag roles such as Queen Rondabellyana in Harlequin and the Red Dwarf [1812], Dame Cecily Suet in Harlequin Whittington, Lord Mayor of London [1814] and Baroness Pomposini in Harlequin and Cinderella; or, The Little Glass Slipper [1820]. This is interesting because the clownish character in pantomime today is supplied by the pantomime dame whilst the clown proper has been relegated to the circus, children’s parties and horror films. However, Grimaldi was also known for performing roles inflected with contemporary racism such as the ‘noble savage’ and ‘wild man’ stereotypes and sometimes using blackface. He impersonated Chinese, Persian, Caribbean and native American characters that were created to make racial otherness the butt of the joke, and was variously billed as ‘Munchikow, a very gifted Eater, Drinker, & afterwards Clown ‘, ‘Cayfacattadhri, the Persian Cook’, ‘Friday a Young Carib’, and ‘Ravin, the Rival Indian’.

Grimaldi enjoyed at least two decades as the undisputed star of the London stage – in some of the pantomimes written at this time, the romantic plot was entirely superseded by the harlequinade so that audiences could experience his entire portfolio of innovative jokes and transformations. Harlequin and the Red Dwarf contained no less than 16 such scenarios that interrupted the romantic plot (based on a tale from the Arabian Nights) and delaying the happily ever after. The most famous of these involved parodies of the Epping hunt and the famous military Hussars. In the latter, Grimaldi would witness a passing Hussar wearing the traditional regalia and be seized with sartorial envy; consequently, he would ludicrously re-construct the Hussar’s costume by adopting coal scuttles for boots, candlesticks for spurs, a bearskin coat and a ladies’ muff and black tippet for hat and moustaches.

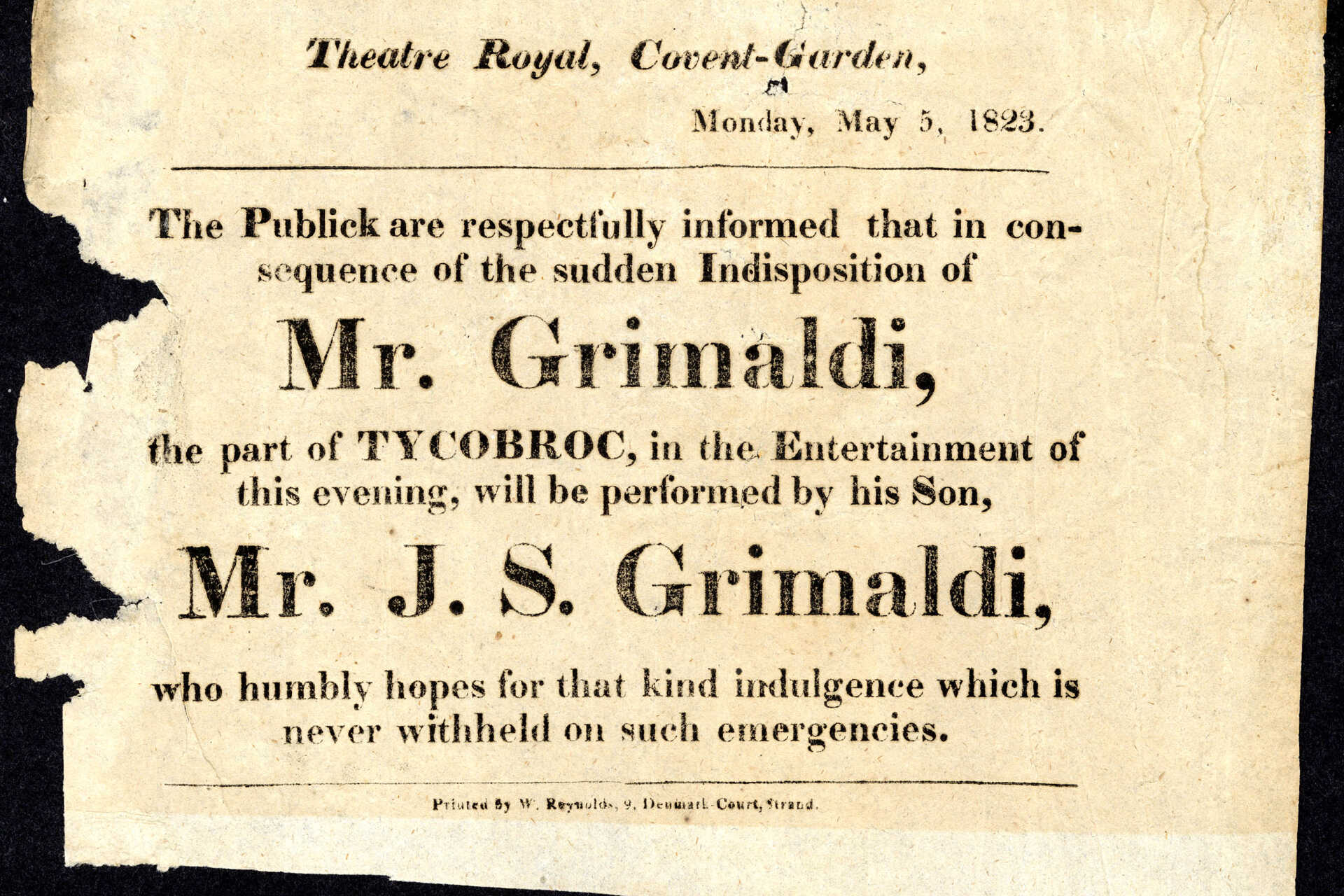

Naturally, the physical nature of such stunts began to take its toll on Grimaldi’s health and in later years his son, J.S. Grimaldi, would have to understudy and step in for him. Grimaldi’s death in 1837 left a vacuum in British theatre and the harlequinades he dominated would eventually be excised from pantomime in the 19th century.