Dr Thirza Loffeld, Community Manager at WildHub and Lecturer in Conservation Social Science at the Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology, obtained her PhD on capacity development for conservation and advises on competency framework and gender equality projects. Her paper has just been published in Oryx—The International Journal of Conservation. She blogs about it here.

‘There are many routes into conservation. The global WildHub community of conservationists of 2500 members across 127 countries is often presented with the following question: “How do I obtain a paid job in conservation?”. Contemporary conservation work involves a wide range of skills, abilities, knowledge and characteristics (also called ‘competences’) and professionals often move into different positions throughout their careers. Once people secure their first paid conservation job, their quest is still not a ‘done deal’, because our progression in knowledge, technological innovations and rapid global change make it imperative for conservation professionals to regularly update their competences.

We initially set out to map which competences conservation professionals require, but soon changed the course of our research, because we realised that a long list of competences would only bring us limited insights and no one professional can attain all competences during their career. Also, many other excellent initiatives have already mapped Competences for protected area practitioners (Appleton, 2016) and for threatened species recovery (Maggs et al., 2021). Instead, we sought to pull out those insights that could be beneficial to anyone working towards nature conservation goals to coach themselves or their organisation in answering the question: how do I (or my organisation) plan and decide on which professional development to dedicate my time, effort and money to?

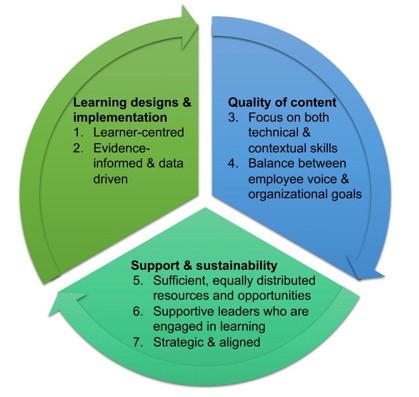

Our findings, summarised in an effectiveness framework (fig 1) can help conservation professionals and conservation organisations assess the quality of existing professional development initiatives and/or design such initiatives themselves. In our study, we used the term professional development to indicate the active process of growth and development an individual undertakes in their professional life, across their entire career, that includes a range of approaches, activities and interventions, as well as the surrounding context and available resources that support this process.

We conducted in-depth interviews with 22 conservation professionals (across 12 different nationalities who had professional work experience in conservation in countries with high biodiversity where capacity and access to resources are limited (i.e. Africa, Latin America and developing regions in Asia)) and examined what made professional development effective in their eyes. We then proceeded with a qualitative thematic analysis identifying commonalities, i.e. themes. After reaching theoretical saturation, meaning that new information resulted in little to no change to the codebook (Hagaman & Wutich, 2017), our findings revealed that little to none of the professional development initiatives which our respondents had experienced or observed, were data-driven and evidence-informed. Some even referred to it as a ‘tick box exercise’ with little to no follow up to check whether participants had actually learned anything. Our study contributes to building an evidence-base to inform current and future professional development initiatives.

Lifelong learning is not a luxury when working in nature conservation: it is a necessity. There are opportunities that are available to conservation professionals. These, however, may not reach everyone in our global conservation workforce, especially those working in remote areas or in isolation, with limited means to connect with other experts. We argue that in our conservation workforce we should create and support a learner’s agency, and provide equal and inclusive opportunities and access to professional development, so that all who work towards nature conservation goals can perform their job to the best of their abilities whilst progressing in their desired career.

As one of our respondents shared under the key theme Strategic and aligned professional development: “Standardize evaluations to whatever extent is possible. Because otherwise we are spending all of our time tweaking, when we could be spending all of our time expanding our reach. So I think that that’s very important and I think we need to share relentlessly.”

Help us distribute our findings across the global conservation workforce by sharing this open access research with your networks.’

This blog was originally published by Oryx.

Read the full paper, Professional development in conservation: an effectiveness framework by A. C. Loffeld, Tatyana Humle, Susan M. Cheyne and Simon A. Black here.