SAC researchers here have found that the teeth of Neanderthal infants formed before birth and developed much sooner than modern human children.

Research led by the University’s School of Anthropology and Conservation has found that the teeth of Neanderthal infants formed before birth and developed much sooner than modern human children -findings that have met with global press interest this week.

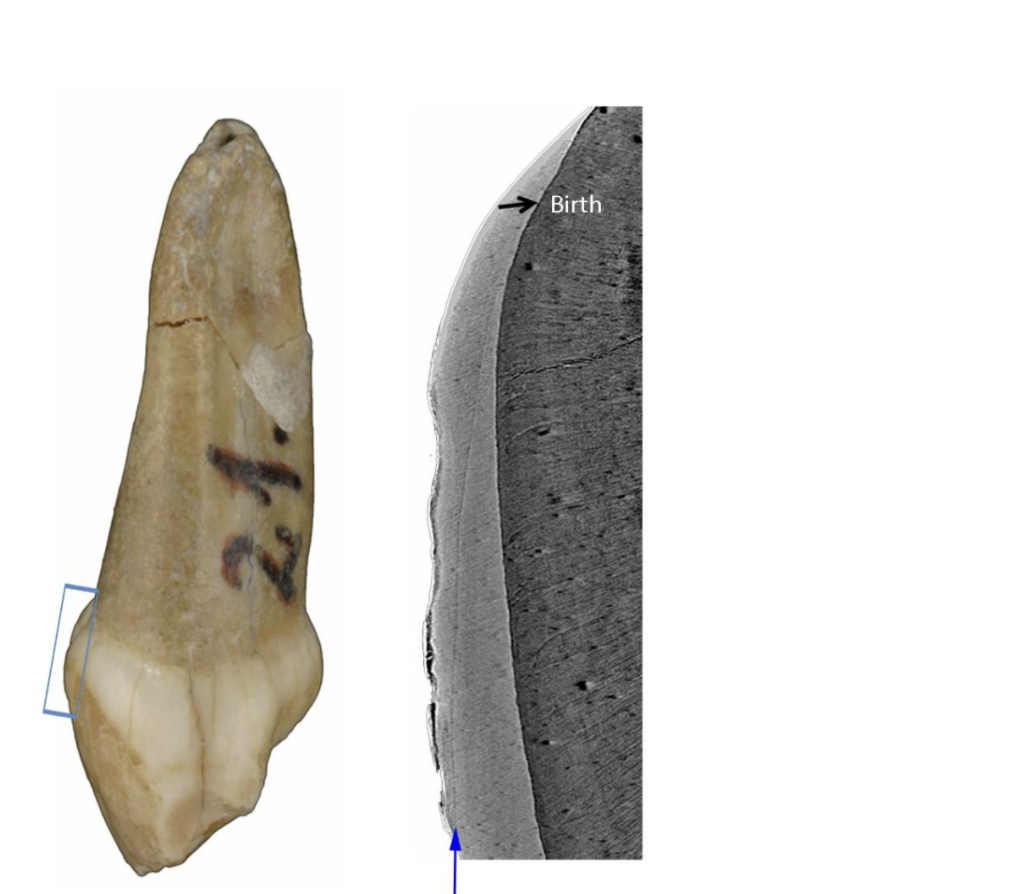

Dr Patrick Mahoney, Dr Alessia Nava and Dr Gina McFarlane examined milk teeth of three Neanderthals that lived 120-130,000 years ago. These teeth start to form before birth and develop as part of a growing organism. They retain a record of their own growth and preserve well in the fossil record. They are time capsules of information.

Modern humans have a slow and extended period of childhood growth but to what extent this pathway was present in Neanderthals is hotly debated. Part of the problem is that we know very little about the growth of Neanderthal infants in the months before and just after birth.

The study published by Proceedings of the Royal Society B, has gained a unique insight into the early growth of these fossil infants.

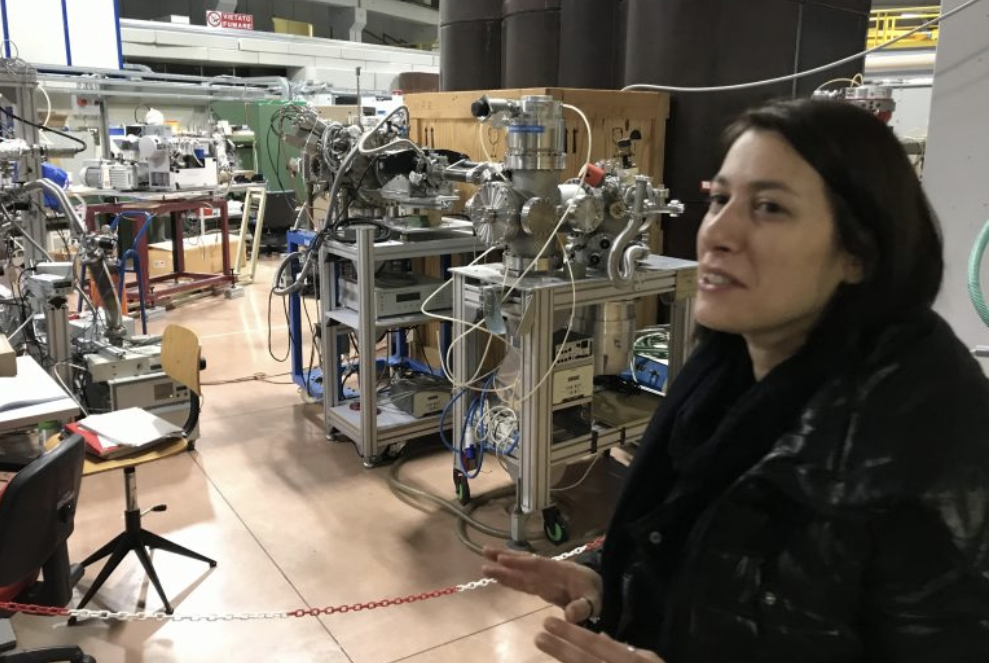

Dr Nava said: ‘We used state-of-the-art non-destructive virtual histology that relies upon synchrotron radiation to examine the inside of the milk teeth. We were able to identify the exact moment these Neanderthals were born.’ Dr Nava, seen above at the Elettra Sincrotone Trieste in Italy, where non-destructive synchrotron radiation computed microtomography was applied to the Neanderthal milk teeth.

Dr Mahoney said: ‘Our study has revealed these Neanderthals had an accelerated patten of dental development compared to a typical modern human child. This likely enabled them to process more demanding supplementary foods at an earlier age compared to a typical modern human child.’

Their finding is consistent with previous evidence that Neanderthals have high brain growth rates by their second year that likely generated large energetic costs.

The team propose ‘these costs could have been offset for Neanderthal infants by their ability to process more demanding supplementary foods at a relatively early age, thereby providing the increased energy rapid brain growth demanded.’

The research paper titled ‘Growth of Neanderthal infants from Krapina (120-130 ka), Croatia ’is published by Proceedings of the Royal Society B. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2021.2079